Click here for a key to the symbols used. An explanation of acronyms may be found at the bottom of the page.

Routing

Routing

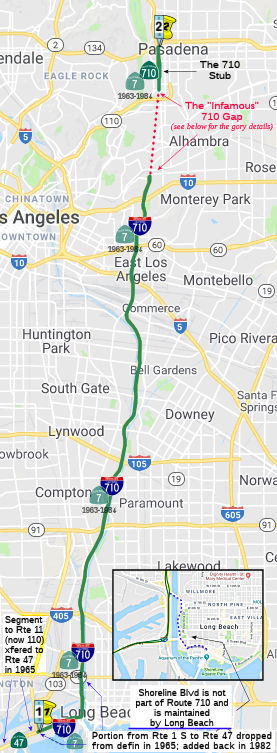

From Route 1 to Route 210 in Pasadena.

From Route 1 to Route 210 in Pasadena.

The route also includes that portion of the freeway between Route 1 and the northern end of Harbor Scenic Drive, that portion of Harbor Scenic Drive to Ocean Boulevard, that portion of Ocean Boulevard west of its intersection with Harbor Scenic Drive to its junction with Seaside Boulevard, and that portion of Seaside Boulevard from the junction with Ocean Boulevard to Route 47.

Section 622.3 of the Streets and Highway Code explicitly authorizes relinquishment of the Pasadena stub, per SB 7 (Chapter 835, 10/21/2019):

(a) Upon a determination by the commission that it is in the best interest of the state to do so, the commission may, upon terms and conditions approved by it, relinquish to the City of Pasadena the portion of Route 710 within the jurisdictional limits of that city, if the department and the city enter into an agreement providing for that relinquishment.

(b) A relinquishment under this section shall become effective on the date following the county recorder’s recordation of the relinquishment resolution containing the commission’s approval of the terms and conditions of the relinquishment.

(c) On and after the effective date of the relinquishment, all of the following shall occur:

(1) The relinquished portion of Route 710 shall cease to be a state highway.

(2) The relinquished portion of Route 710 shall be ineligible for future adoption under Section 81.

(3) The City of Pasadena shall ensure the continuity of traffic flow on the relinquished portion of Route 710.

Note: SB 7 modified the definition of the route in the Freeway and Expressway system (Article 2 of the SHC) to, as of 1/1/2024, delete the gap between Alhambra Ave in Los Angeles and California Street in Pasadena (i.e., the space between the stubs) from the freeway and expressway system. This means that if the state wants a freeway in that segment, they have to start the route adoption process from scratch. SB 7 does not authorize relinquishment of the Alhambra stub, nor any portion of the unconstructed gap that is not in the City of Pasadena.

In June 2022, the CTC authorized relinquishment of right of way in the

city of Pasadena along State Route 710 between Columbia Street and Union

Street (15 segments, 07-LA-710-PM T30.9/R32.5), under terms and conditions

as stated in the relinquishment agreement dated June 1, 2022, determined

to be in the best interest of the State. Authorized by Chapter 835,

Statutes of 2019, which amended Section 622.3 of the Streets and Highways

Code. Note: The relinquishment resolution does not appear to include

the portion between where Route 210 transitions off and Union Street, so

it is unclear if that now smaller stub will remain part of Route 710, or

will be classified as alternative mileage of Route 210. Further, the

relinquishment does not include the Route 134 transition ramps or the

Route 210 transition ramps, which are not part of Route 710.

(Source: June 2022 CTC Agenda, Agenda Item

2.3c.(2), including yellow and pink supplementary material)

Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage HistoryUntil July 1, 1964, this routing was signed as Route 15. When the Route 15 signage had to be applied to the new Interstate (I-15) that had previously been US 91 (between I-10 and Las Vegas), the routing was renumbered as Route 7:

In 1963, Route 7 was defined as "from Route 11 [Present-Day Route 110] in San Pedro to Route 210 in Pasadena via Long Beach and including a bridge, with at least four lanes, from San Pedro at or near Boschke Slough to Terminal Island." In 1965 the southern end was truncated by Chapter 1372, transferring the San Pedro portion and bridge to Route 47, and dropping the portion S of Route 1 to Route 47 from the definition of the route. This left the route definition as "from Route 1 to Route 210 in Pasadena." (which harkened back, origin-wise, to the original 1933 definition of LRN 167).

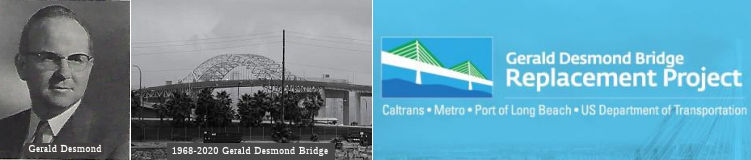

On October 19, 1965, construction broke ground on the Gerald Desmond

Bridge along Seaside Boulevard in Long Beach. The structure was a

direct replacement for the 1944 Terminal Island Pontoon Bridge. The

intent of the Gerald Desmond Bridge was to provide a direct link for

Terminal Island traffic to reach the Long Beach Freeway. The Gerald

Desmond Bridge was completed during June 1968. The Gerald Desmond

Bridge was a five lane through arch span which was 5,134 feet long.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

In 1982, Chapter 914 extended the definition to explicitly add back in the portion of the freeway between Route 1 and the northern end of Harbor Scenic Drive, that portion of Harbor Scenic Drive to Ocean Boulevard, that portion of Ocean Boulevard west of its intersection with Harbor Scenic Drive to its junction with Seaside Boulevard, and that portion of Seaside Boulevard from the junction with Ocean Boulevard to Route 47. It was noted that this extension didn't become operative unless the commission approves a financial plan that included a cost estimate and the source of funding to make the route for the portion S of Route 1 and any proposed improvements. Note: The northern end of Harbor Scenic Drive is where 7th Street veers to the E across the Shoemaker Bridge; this means that the Shoemaker Bridge and the "freeway" portion running down to the Long Beach Pier was NOT part of the State Highway System.

In 1984, Chapter 409 defined Route 710 as "Route 1 to Route 210 in Pasadena." The additional conditions regarding the Harbor Scenic Drive and the financial conditions were also transferred. This reflected the approval of Route 7 as 139(a) non-chargable interstate for continuity of numbering with Route 10 (I-10), off of which it spurs. [One might argue that it could have been considered a loop route around the center of the city, and as such, would more appropriately have an (even digit)05 number. However, all of the (even-digit)05 numbers are in use: I-205 (Sacramento), I-405 (Los Angeles), I-605 (Los Angeles), I-805 (San Diego).]

The legislative description of Route 710 transferred from Route 7 still included the portion between Route 1 and the northern end of Harbor Scenic Drive, a portion of Harbor Scenic Drive to Ocean Blvd, a portion of Ocean Blvd west of its intersection with Harbor Scenic Drive to its junction with Seaside Blvd, and a portion of Seaside Blvd from the junction with Ocean Blvd to Route 47. For a long time, this was ambiguously signed; it was signed as part of the route after planned port-related improvements by the cities of Long Beach and Los Angeles were completed. The segment from Ocean Blvd to Route 1 is non-chargeable 139(b) mileage. There are some indications that this segment was signed with a state, not Interstate, shield, at least until it was upgraded to full freeway as part of updates in the 2010s..

To make it clear: The south end of I-710 follows the west riverbank, not the east riverbank (into downtown Long Beach, across the Shoemaker Bridge). Caltrans only maintains the east riverbank spur until the 9th Street exit; the City of Long Beach has control of the road (Shoreline Drive) past this point (however, ownership of the Shoemaker Bridge will be changing post 2020). Route 710 is supposed to follow the Long Beach Freeway down to the Harbor Scenic Drive cutoff south of Anaheim Street (now constructed freeway), and then follow Harbor Scenic Drive (again, now constructed freeway) to Ocean Blvd (Seaside Freeway) and then follow Ocean Blvd across the Gerald Desmond Bridge to the junction of Ocean and Seaside Blvds with the Terminal Island Freeway. According to Caltrans, once the replacement for the Gerald Desmond bridge is completed, Ocean Boulevard will be the westward extension of Route 710 to the Terminal Island Freeway (Route 47). Ocean Boulevard is currently operated by the City of Long Beach. After the bridge is completed, it and the segment of Ocean Boulevard between Route 47 and Route 710 will be adopted into the State Highway System and the roadway transferred to Caltrans. The extension across the Shoemaker Bridge (7th Street) towards the Queen Mary, Cruise Terminals, Aquarium and the parks is Shoreline Blvd (although the Queen Mary is also accessible via S Harbor Scenic Drive).

[In fact, the state did not construct the portion of I-710 S of Route 1, across the Shoemaker Bridge That portion was constructed to freeway standards by the City of Long Beach. The construction cost was $12 million.]

On September 23, 1983, Caltrans submitted an application to add Route 7

and the Long Beach Freeway from Route 1 in Long Beach to I-10 to the

Interstate System as I-710. The American Association of State

Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO) approved the addition of I-710

on May 24, 1984. During October 1984, the FHWA would approve the

addition of I-710 and the Long Beach Freeway from Route 1 to I-10 as

non-chargeable Interstate. On December 8, 1984, AASHTO would approve a

second request by Caltrans to extend I-710 to Ocean Boulevard at the Port

of Long Beach. Note: The portion S of Ocen Blvd, and the

portion N of I-10, are not part of the I-710 designation.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

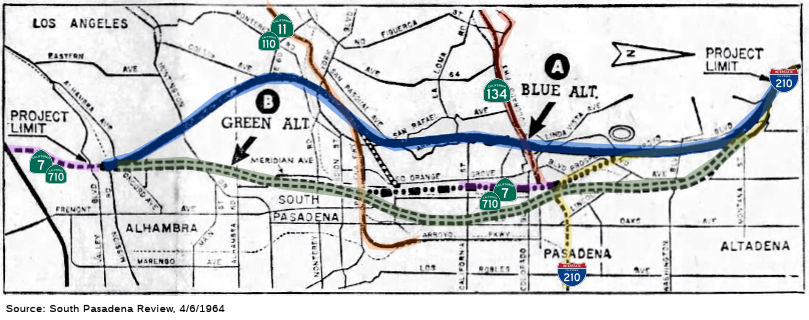

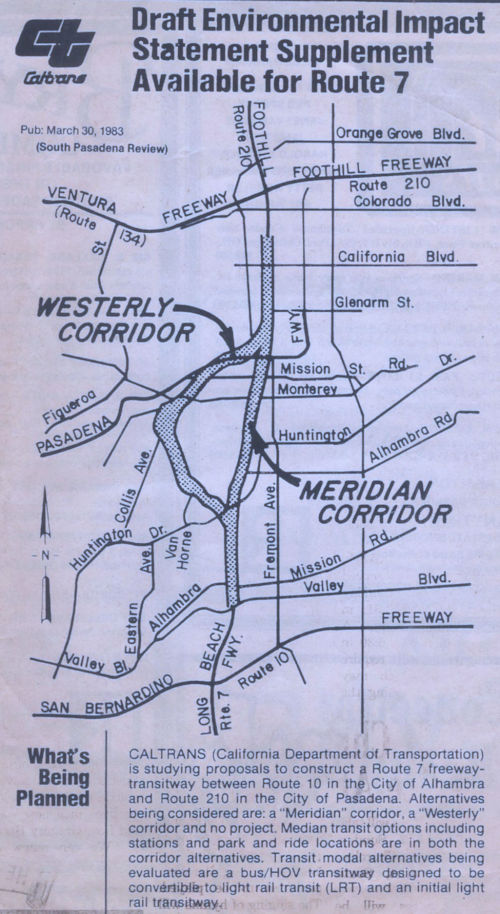

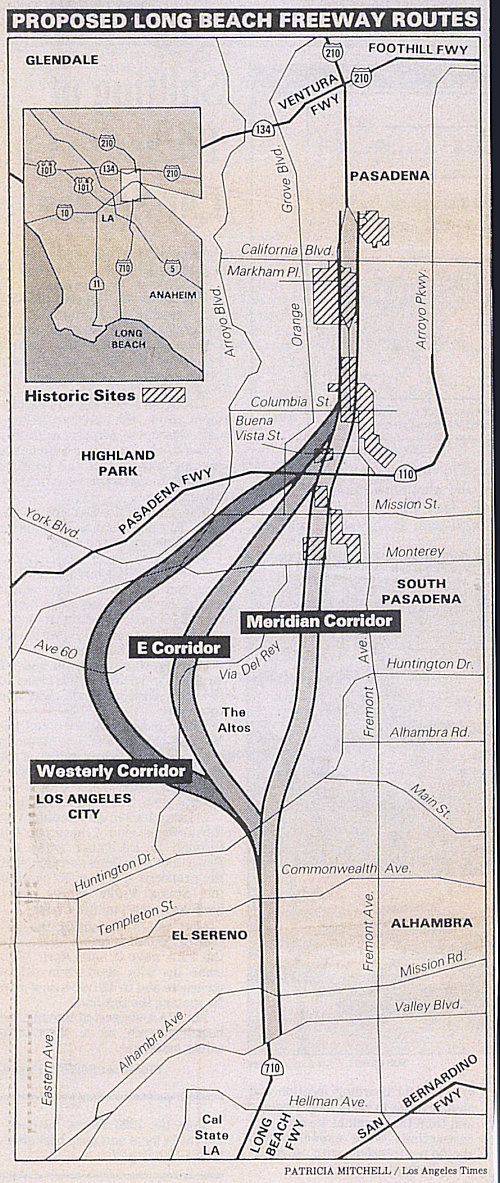

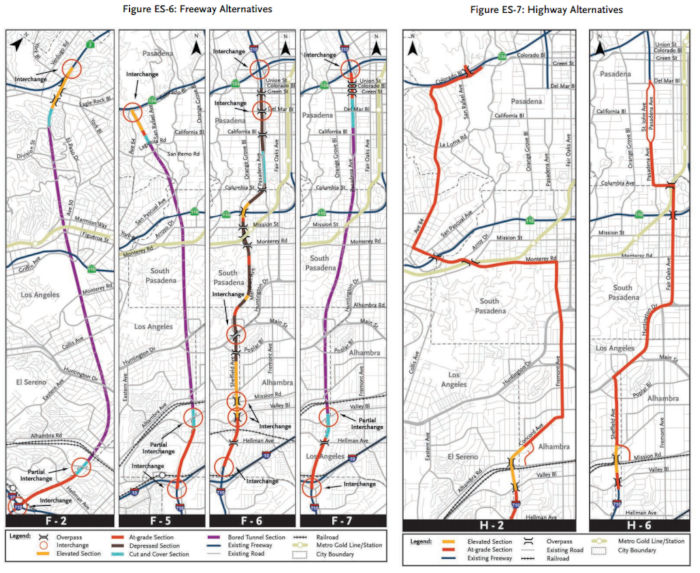

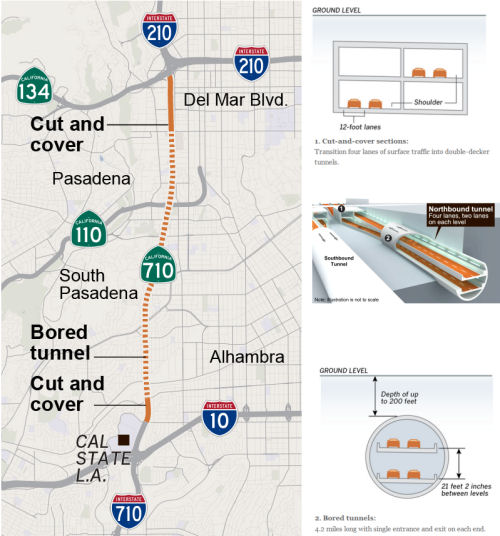

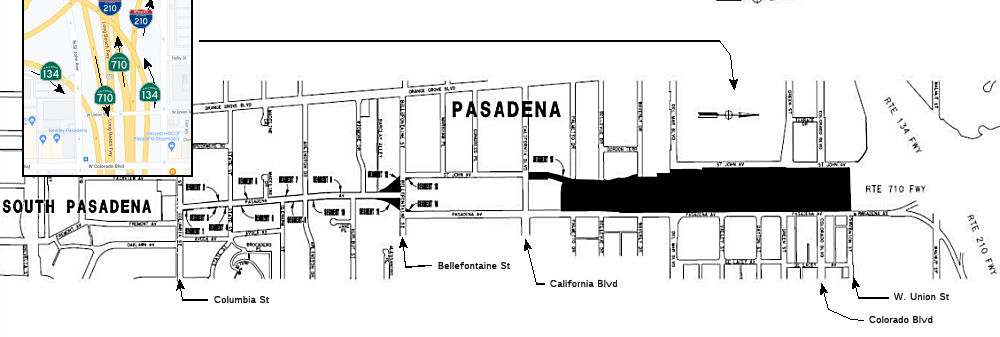

The route is unconstructed and unsigned between Columbia St and I-210 in Pasadena, although there is a stub of Route 710 (not Interstate)

at the Route 134/I-210 junction. There has been intense local opposition

to completion of this freeway as it would have a potentially adverse

impact on historic homes in Pasadena and South Pasadena. On the other

hand, it is a critical link in the overall Southern California freeway

system. The traversable route is... oh hell, just read the mishegas below

in the STATUS section.

The route is unconstructed and unsigned between Columbia St and I-210 in Pasadena, although there is a stub of Route 710 (not Interstate)

at the Route 134/I-210 junction. There has been intense local opposition

to completion of this freeway as it would have a potentially adverse

impact on historic homes in Pasadena and South Pasadena. On the other

hand, it is a critical link in the overall Southern California freeway

system. The traversable route is... oh hell, just read the mishegas below

in the STATUS section.

In 2013, Chapter 525 (SB 788, 10/9/13) deleted the words in the route definition about a financial plan:

(b) Subdivision (a) shall not become operative, and this section shall be repealed on January 1, 1985, unless the commission approves, not later than December 31, 1984, a financial plan, which is submitted to them by the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission not later than January 1, 1984.

(c) The financial plan shall be prepared in cooperation with the department and shall include, but not be limited to, a cost estimate and the source of funding to make the route changes in subdivision (a) and any proposed improvements.

In 2019, both AB 29 (Chapter 791, 10/21/2019) and SB 7 (Chapter 835, 10/21/2019) were chaptered, and SB 7, being chaptered last, took precedence. SB 7 changed the definition of the route in the freeway and expressway system to prepare for relinquishment of the Route 710 gap (note that it did not change the definition of the route itself):

(2) Route 1 near the City of Long Beach to Route 10 near the City of Alhambra.

(3) Route 10 near the City of Alhambra to Route 210 near the City of Pasadena.

SB 7 explicitly requires, that as of 1/1/2024, items (2) and (3) are changed to

(2) Route 1 near the City of Long Beach to

Route 10 near the City of AlhambraAlhambra Avenue in the City of Los Angeles.(3)

Route 10 near the City of AlhambraCalifornia Boulevard in the City of Pasadena to Route 210.

This explicitly deletes the unconstructed portion of Route 710 from the freeway and expressway system. Further, SB 7 added Section 622.3 to the SHC to read:

(a) Upon a determination by the commission that it is in the best interest of the state to do so, the commission may, upon terms and conditions approved by it, relinquish to the City of Pasadena the portion of Route 710 within the jurisdictional limits of that city, if the department and the city enter into an agreement providing for that relinquishment.

(b) A relinquishment under this section shall become effective on the date following the county recorder’s recordation of the relinquishment resolution containing the commission’s approval of the terms and conditions of the relinquishment.

(c) On and after the effective date of the relinquishment, all of the following shall occur:

(1) The relinquished portion of Route 710 shall cease to be a state highway.

(2) The relinquished portion of Route 710 shall be ineligible for future adoption under Section 81.

(3) The City of Pasadena shall ensure the continuity of traffic flow on the relinquished portion of Route 710.

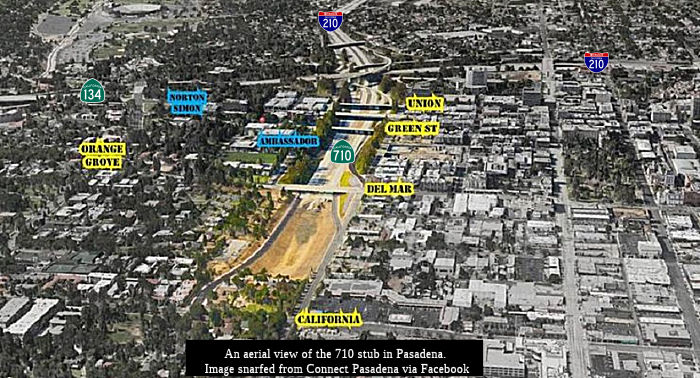

In May 2022, it was reported that the Pasadena City Council voted to

approve their end of a contract with Caltrans to reclaim a portion of the

land that Caltrans had already purchased for extending Route 710

– land located between Union Street and Columbia Street. The

California Transportation Commission needs to approve the transfer, but

with Caltrans and the city in agreement, that last hurdle could well be

little more than a formality. Without this land, the 710 gap closure

project will be so dead that it can’t be resurrected. On Wednesday,

June 29, the California Transportation Commission voted to officially

enable Pasadena to redesign the “710 Stub,” a corridor between

the 710 and the 210. The approval of this deal does not include the

parcels of land north of California Blvd that include residential and

institutional tenants. According to the Roberti Bill, existing tenants

will have first right of refusal, but none of this legislation addresses

how these properties will be sold. It seems that the City is waiting to

ascertain which tenants will purchase their properties before establishing

a plan for selling the properties and for the undeveloped stub of land,

known colloquially as The Ditch.

(Source: 669xGxaLjwqejoaIaV13l5bsLPKY9BVt4CtqdV6KUPa6lUIBf-O3IU">Streetsblog LA, 5/4/2022; Colorado

Boulevard . Net, 5/7/2022)

In June 2022, the CTC authorized relinquishment of right of way in the

city of Pasadena along State Route 710 between Columbia Street and Union

Street (15 segments, 07-LA-710-PM T30.9/R32.5), under terms and conditions

as stated in the relinquishment agreement dated June 1, 2022, determined

to be in the best interest of the State. Authorized by Chapter 835,

Statutes of 2019, which amended Section 622.3 of the Streets and Highways

Code.

(Source: June 2022 CTC Agenda, Agenda Item

2.3c.(2), including yellow and pink supplementary material)

The following freeway-to-freeway connections were never constructed:

Pre 1964 Signage History

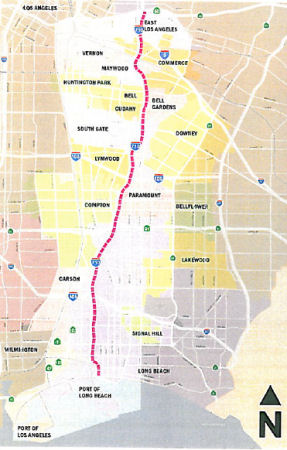

Pre 1964 Signage HistoryThis was formerly signed as Route 15, and was LRN 167, defined in 1933. Until the construction of the freeway, Route 15 ran between Pacific Coast Highway and US 99 along Atlantic Blvd. In 1964, the freeway routing was renumbered as Route 7, and was later renumbered as Route 710 and I-710.

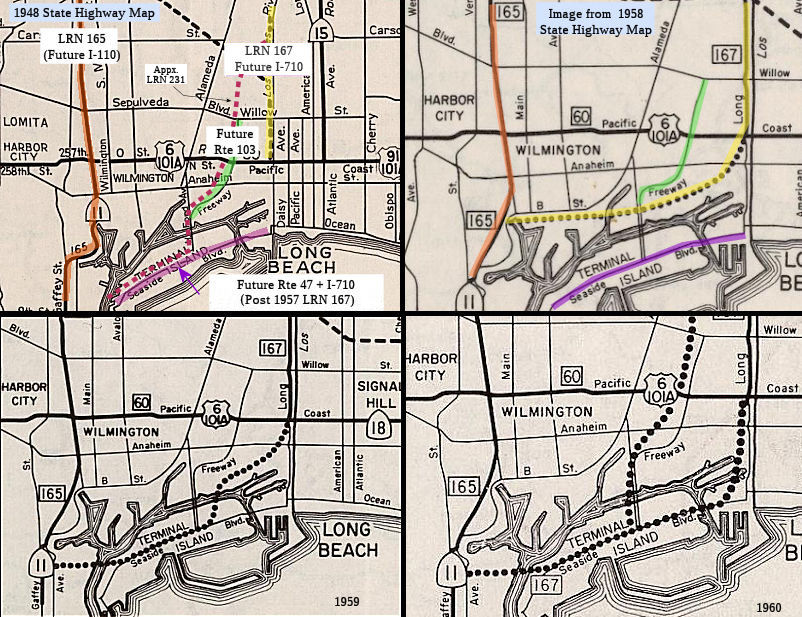

The history of what became I-710 in the Port of Los Angeles is a bit convoluted, and centers around LRN 167, LRN 231, and the future Route 47 and Route 103 as well.

In 1933, the route from "Long Beach via Atlantic Boulevard to [LRN 26] near Monterey Park" was added to the state highway system. In 1935, it was added to the highway code as LRN 167, with the same routing. Note the starting point of the route was not the Port of Los Angeles -- it is Pacific Coast Highway (US 101A, US 6) in the city of Long Beach.

The alignment of Sign Route 15/LRN 167 as of 1935 began at US 101A/LRN 60

(formerly Sign Route 3) in Long Beach, and followed Atlantic Avenue north

to Olive Street near Clearwater, Hynes and Compton. Sign Route 15/LRN 167 crossed the Los Angeles River via Olive Avenue and rejoined

Atlantic Avenue. North of Compton the route followed Atlantic Avenue to US 99-US 60-US 70/LRN 26 in Monterey Park. In 1938, Sign Route 15/LRN 167 was

realigned onto the new Los Angeles River Bridge between Artesia Avenue and

Compton Boulevard, making the two segments of Atlantic Avenue continuous.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

During 1944 the eastern half of Terminal Island was connected to Long

Beach via pontoon bridge. The Pontoon structure span was intended to

be a temporary aid to facilitate movement to the Terminal Island Naval

Facilities. The Terminal Island Pontoon Bridge connected Seaside

Boulevard to Harbor Scenic Drive in Long Beach.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

In 1947 (1st ex. sess.), Chapter 11 adjusted LRN 167. It kept the same endpoints, but introduced a discontinuity at (former) Route 245/US 101: "(a) Long Beach to [LRN 166]; (b) (a) above, near Los Angeles River to [LRN 26] via Atlantic Boulevard"

In 1949, Chapter 1467 combined the segments of LRN 167 and extended the route to [LRN 205] (Pasadena Freeway): "Long Beach to [LRN 205] in South Pasadena"

In 1949, Chapter 1261 defined LRN 231. This was a

proposed freeway connection between then Route 11 and the Los Angeles

River Freeway (then Route 15, now I-710) that would be an extension of the

Federally-built Terminal Island Freeway (which wasn't yet in the state

highway system). It was contingent on Federal funding for the portion on

the mainland, and state funding for the non-mainland (Terminal Island)

portion, which never materialized. See Route 103 for the details. The key

points in the definition were that it was “via the mainland portion

of Long Beach Outer Harbor and Terminal Island,” and “If funds

from sources other than state highway funds have not been made available

for the construction on all portions of said [LRN 231] that are not on the

mainland prior to January 15, 1953, said [LRN 231] shall on that date

cease to be a state highway and this section shall have no further force

or effect.”

In 1949, Chapter 1261 defined LRN 231. This was a

proposed freeway connection between then Route 11 and the Los Angeles

River Freeway (then Route 15, now I-710) that would be an extension of the

Federally-built Terminal Island Freeway (which wasn't yet in the state

highway system). It was contingent on Federal funding for the portion on

the mainland, and state funding for the non-mainland (Terminal Island)

portion, which never materialized. See Route 103 for the details. The key

points in the definition were that it was “via the mainland portion

of Long Beach Outer Harbor and Terminal Island,” and “If funds

from sources other than state highway funds have not been made available

for the construction on all portions of said [LRN 231] that are not on the

mainland prior to January 15, 1953, said [LRN 231] shall on that date

cease to be a state highway and this section shall have no further force

or effect.”

In 1951, Chapter 1562 truncated the terminus of LRN 167 to Huntington Drive: "… to Huntington Drive."

In 1951, it was announced that the planned Los Angeles River Freeway of

Sign Route 15/LRN 167 had been renamed the "Long Beach Freeway."

That name had been adopted by a Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors

resolution. The concept of the Long Beach Freeway started 14 years

prior by the Long Beach City Engineering Department. The Long Beach

Freeway had a planned southern terminus near Anaheim Street in Long Beach

which would connect to the vicinity of the Terminal Island Pontoon Bridge.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

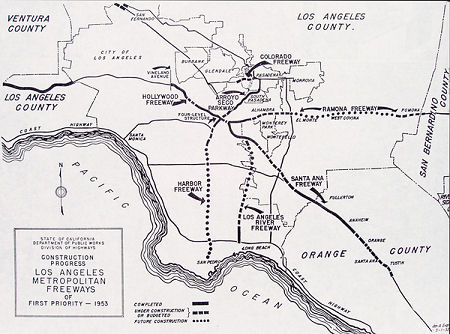

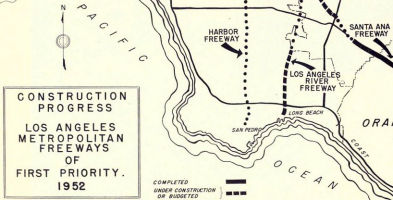

Construction started on the Long Beach Freeway around 1952, with the

first construction unit between US 101A/LRN 60 to 23rd Street. The

planned opening was July 1954. The city of Long Beach retained

right-of-way to construct an extension of the Long Beach Freeway south of

US 101A towards Terminal Island. The route of the Long Beach Freeway from

the Santa Ana Freeway to Huntington Drive was adopted by the California

Highway Commission on July 24, 1953.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

By 1954, LRN 231 had disappeared, eliminating the connection between LRN 167 and LRN 165.

Sign Route 15/LRN 167 was relocated onto the completed Long Beach Freeway

from US 101A/LRN 60 north to Atlantic Avenue near Compton by 1955.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

In 1957, Chapter 1911 extended the origin of LRN 167 to [LRN 165] (Harbor

Freeway): “[LRN 165] in San Pedro Long Beach

to Huntington Drive via Long Beach”. This provided a

different routing to connect the two highways distinct from the Terminal

Island Freeway (former LRN 231) routing. But as one can see from the map,

the routing wasn't quite the current routing yet.

Also in 1957, approximately 10 of the 16.5 miles of the state-owned

portion (LRN 167) of the Long Beach Freeway from US 101A/LRN 60 to the

Santa Ana Freeway (US 101/LRN 166) was completed. The extension

north to Huntington Drive was originally known as the Concord Freeway when added to the State Highway System during 1951. The Concord Freeway was reassigned to

the Long Beach Freeway corridor by the California Highway Commission

during November 1954.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

In 1958, Chapter 74 added the San Pedro-Terminal Island Bridge to LRN 167: "[LRN 165] in San Pedro to Huntington Drive via Long Beach, and including a bridge with at least four lanes from San Pedro at or near Boschke Slough to Terminal Island".

The proposed Terminal Island Bridge appears as a concept drawing in the

May/June 1959 California Highways & Public Works. The article

notes the California Highway Commision on April 30, 1959, decided to fund

the Terminal Island Bridge as a tolled facility. The Terminal Island

Bridge project area was approximately 7,400 feet, and would be constructed

a short distance north of the Terminal Island Ferry route in San

Pedro. The Terminal Island Bridge was planned to tie into Seaside

Avenue on Terminal Island near Mormon Street, and was planned as a

component of the Long Beach Freeway.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

In 1959, Chapter 1062 extended LRN 167 to LRN 9: "[LRN 165] in San Pedro

to Huntington Drive [LRN 9] in Pasadena via Long

Beach, and including a bridge with at least four lanes from San Pedro at

or near Boschke Slough to Terminal Island"

By 1960, the routing in the port had assumed the current approach running to Route 47 (portions of which were LRN 167 across the Vincent Thomas Bridge, added in 1963).

In 1960, it was noted that the Terminal Island Bridge was adopted as part

of a 1.6-mile freeway by the California Highway Commission on August 28,

1959. It was also noted construction by the city of Long Beach on

their portion of the Long Beach Freeway had reached Broadway by 1959, but

that the Long Beach Freeway designation as officially defined ended at US 101A. The bridge was eventually renamed the Vincent Thomas Bridge (see

Route 47), and made part of the Seaside Freeway. Despite the Vincent

Thomas Bridge no longer being part of the Long Beach Freeway corridor, it

was still part of LRN 167 and Sign Route 15.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

In the 1964 renumbering, Sign Route 15 became Route 7, defined as "From Route 11 in San Pedro to Route 210 via Long Beach and including a bridge, with at least four lanes, from San Pedro at or near Boshlke Slough to Terminal Island." In 1965, the Vincent Thomas Bridge was moved to Route 47, and Route 7 was adjusted to start at Route 1.

Note that the actual construction of the freeway routing for future Route 710 between Pacific Coast Highway and Route 47 did not occur for many years, and was primarily a result of a land-swap with the City of Long Beach where a portion of Seaside Blvd was given to the state in exchange for the portion of Route 103 N of Pacific Coast Highway.

According to KCET, Route 710 can be traced back to the "Great Free-Harbor

Fight" of the 1890s, where Los Angeles City officials helped solidify the

port in San Pedro by annexing a sixteen-mile "shoestring district" that

made the harbor a legal part of the city. Los Angeles also spent $10

million on harbor improvements, and proposed the construction of a truck

highway for developing the port. Although millions of dollars were poured

into the port's infrastructure by the early 1940s, not much was done to

facilitate any port highway. Before state planners (responsible for

designing state freeways) could map out a freeway from the ports to the

Los Angeles metropolis, harbor interest had already begun making

preliminary maps as early as 1921; though nothing materialized. Despite a

1939 California Freeway Law that gave "the state broad powers of land

acquisition for the construction [and financing] of freeways," it was the

City of Long Beach that took it upon themselves to plan, construct, and

finance the port highway, to be called the Los Angeles River Freeway

because it hugged the natural waterways that were once the lifeblood of

the founding families. So, Route 710 is essentially the child of the City

of Long Beach, superseding legal precedents that had placed the state of

California, not local governments, as the principal investors and

designers of state freeways (note that Route 710 was originally just a

state route: initially Route 15, and then later renumbered as Route 7 in

1964. It was eventually renumbered as non-chargable I-710).

(Source: KCET — History of the 710 Freeway, 2/12/2014)

An August 1941 report issued by the Regional Planning Commission of Los

Angeles County entitled “A Report on the Feasibility of a Freeway

Along the Channel of the Los Angeles River” proposed a

four-lane roadway on each levee from Anaheim Street in Long Beach north to

Sepulveda Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley; excepting between Soto

Street and Dayton Street in downtown Los Angeles, where, due to a lack of

right-of-way along the river, the alignment matches the future alignment

of the US 101 portion of the Santa Ana Freeway. There is no mention in the

report of a master plan of freeways like that issued in 1947, although the

maps showed connections to the already-completed Arroyo Seco Parkway and

the proposed Ramona and Rio Hondo Parkways.

(Source: Daniel Thomas)

In the 1930s and 1940s, before the route was adopted as a freeway routing, the cities of Long Beach and Los Angeles knew the route was coming, and began preserving right of way along the Los Angeles River for the future route. This saved significant money for right of way acquisition.

By 1949, Long Beach had already invested

$1,000,000 on the freeway, and the city's Chamber of Commerce made

reoccurring appeals to the California State Highway Commission for

continued support. This unorthodox practice of an independent agency

developing their own freeway was not unnoticed by the California Division

of Highways, the precursor to Caltrans. "The southerly extension of the

Los Angeles River Freeway," as noted in their bi-monthly publication

California Highway and Public Works, "requires special mention because the

construction work now in progress by the City of Long Beach is the only

instance since World War II of another governmental agency carrying out

the construction and financing of a complete unit on the Los Angeles

Metropolitan Freeway System." Several years before the Los Angeles River

Freeway was legislated into the California State Highway System in 1947,

Long Beach planners received general counsel from the Los Angeles County

Regional Planning Commission, but were largely free from state

interference when designing the freeway. Long Beach Harbor authorities

even financed a "major portion" of the freeway, in what the state

acknowledged was a "staggering" amount, a figure that reached

approximately $12 million by 1953, according to a the Division of

Highways. Essentially, the freeway was constructed to serve business

generated by the harbor and local industry; commuter vehicular traffic was

secondary, at best. Any negative impact to communities during or after the

construction of the freeway was seen as all but non-existent. Segments of

Route 710 eventually connected with I-5, in the heart of the manufacturing

district in East Los Angeles, by the 1960s. This district housed extensive

intermodal railyards from the Union Pacific, and the Atchison, Topeka and

Santa Fe Railroad. As such, some of the early freeway construction of

Route 710 required multiple bridges over eighteen railroad tracks,

requiring 1,100 parcels of real estate. Route 710 cut through established

communities, such as East Los Angeles and City of Commerce, that already

housed dozen of freeway lane miles. In East Los Angeles, nearly 11,000

residents were displaced due to freeway construction and widenings,

consuming some 7% of total land area.

By 1949, Long Beach had already invested

$1,000,000 on the freeway, and the city's Chamber of Commerce made

reoccurring appeals to the California State Highway Commission for

continued support. This unorthodox practice of an independent agency

developing their own freeway was not unnoticed by the California Division

of Highways, the precursor to Caltrans. "The southerly extension of the

Los Angeles River Freeway," as noted in their bi-monthly publication

California Highway and Public Works, "requires special mention because the

construction work now in progress by the City of Long Beach is the only

instance since World War II of another governmental agency carrying out

the construction and financing of a complete unit on the Los Angeles

Metropolitan Freeway System." Several years before the Los Angeles River

Freeway was legislated into the California State Highway System in 1947,

Long Beach planners received general counsel from the Los Angeles County

Regional Planning Commission, but were largely free from state

interference when designing the freeway. Long Beach Harbor authorities

even financed a "major portion" of the freeway, in what the state

acknowledged was a "staggering" amount, a figure that reached

approximately $12 million by 1953, according to a the Division of

Highways. Essentially, the freeway was constructed to serve business

generated by the harbor and local industry; commuter vehicular traffic was

secondary, at best. Any negative impact to communities during or after the

construction of the freeway was seen as all but non-existent. Segments of

Route 710 eventually connected with I-5, in the heart of the manufacturing

district in East Los Angeles, by the 1960s. This district housed extensive

intermodal railyards from the Union Pacific, and the Atchison, Topeka and

Santa Fe Railroad. As such, some of the early freeway construction of

Route 710 required multiple bridges over eighteen railroad tracks,

requiring 1,100 parcels of real estate. Route 710 cut through established

communities, such as East Los Angeles and City of Commerce, that already

housed dozen of freeway lane miles. In East Los Angeles, nearly 11,000

residents were displaced due to freeway construction and widenings,

consuming some 7% of total land area.

(Source: KCET — History of the 710 Freeway, 2/12/2014)

The route was originally to be named the "Los Angeles River Freeway"; in

1952, the LA Board of Supervisors approved renaming it the Long Beach

Freeway. The initial 2.3-mile freeway segment opened between Pacific Coast

Highway and 223rd Street on December 10, 1952. Separation structures have

been built at Pacific Coast Highway and at Willow Street. Completion of

the second section was in 1953.

(Source: Metro Library: This Day in Transportation History, 12/10/2019; January-February1953

California Highways and Public Works)

As defined in 1933, LRN 167 (future Route 7 / I-710) extended north only to "[LRN 26] near Monterey Park", which was US 60 / US 70 / US 99 (future I-10).

In 1949, Chapter 1467 extended LRN 167 to [LRN 205] (Pasadena

Freeway): "Long Beach to [LRN 205] in South Pasadena"

In 1951, Chapter 1562 truncated the terminus of LRN 167 to Huntington

Drive: "… to Huntington Drive."

In 1959, Chapter 1062 extended LRN 167 to LRN 9 (Route 118 at the time, future I-210): "[LRN 165] in San Pedro to [LRN 9] in Pasadena via Long Beach, and including a bridge with at least four lanes from San Pedro at or near Boschke Slough to Terminal Island". As such, the plans for the extension to the future I-210 Foothill Freeway were on the books since 1959.

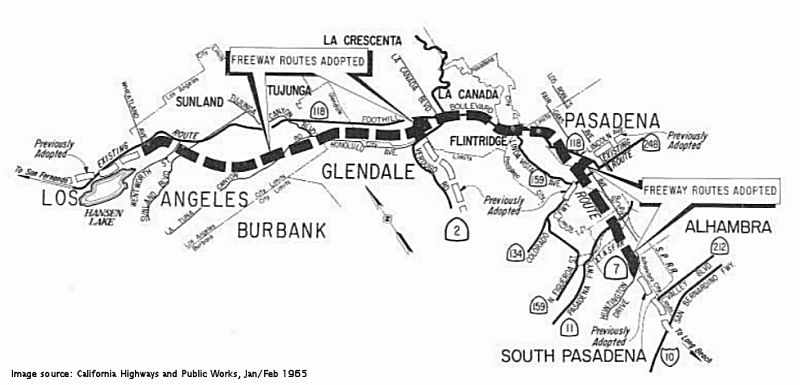

The Division of Highways began location studies on the Pasadena extension

of LRN 167 and the Long Beach Freeway during 1960. On April 21,

1960, the State formally notified the cities of Pasadena, South Pasadena

and Alhambra that studies were being initiated for the location of the

Long Beach Freeway from Huntington Drive to the Foothill Freeway.

The March/April 1961 California Highways & Public Works notes Senate

Bill 480 established a 1.7-mile extension of the Long Beach Freeway from

the city of Alhambra to near the junction of the Foothill-Pasadena

Freeways. The Long Beach Freeway extension was under advanced

planning along with the north/south leg of the Foothill Freeway through

Pasadena.

(Source: Gribblenation Blog (Tom Fearer), "Interstate 710", 8/26/2023)

Status

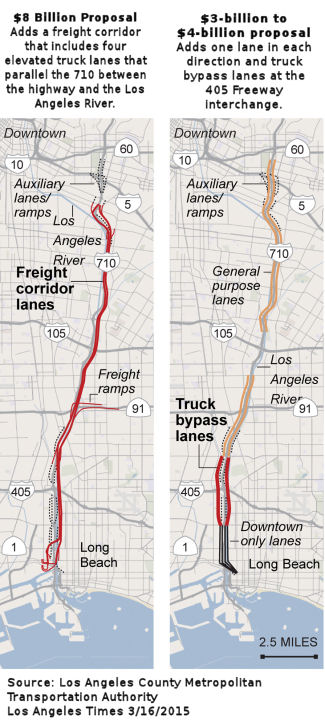

StatusIn June 2015, it was reported that, in its latest analysis of California

Highway Patrol data from 2012, the Southern California Associations of

Governments (SCAG) included sections of this route in its list of freeway

sections in L.A. County and the Inland Empire with the highest

concentrations of truck crashes per mile annually. These sections were

I-710 at Route 60 in the East L.A. Interchange, with 7.2 accidents; I-710

between I-105 and the Route 91, with 5.8 accidents; the convergence of

Route 60 and Route 57, with six crashes; and I-5 between I-710 and I-10,

also in the East L.A. Interchange, with 6.6 crashes. The analysis also

identified that the second-highest number of truck crashes can be found on

three parts of Route 60 between I-605 and I-710, between the I-15 and

Route 71 — the Chino Valley Highway, formerly known as the Corona

Expressway — and immediately east of I-215. That category also

includes I-10 between Route 71 and I-215, I-605 between Route 60 and I-10,

and Route 710 between Route 91 and the Port of Long Beach as well as

between I-5 and I-105. With the nation's largest combined harbor, the Los

Angeles area also is one of the busiest in the country, if not the world,

for trucking. I-710 often handles more than 43,000 daily truck trips,

Route 60 up to 27,000 and I-5 about 21,500, according to Caltrans. In June

2015, it was also reported that Caltrans and Metro are studying elevated

truck lanes for I-710 or rearranging lanes so trucks have a bypass lane.

(Source: LA Times, 6/2/2015, LAMagazine,

6/2/2015)

Port of Los Angeles and Long Beach

Gerald Desmond Bridge / Long Beach International Gateway Bridge (07-LA-710 3.7/6)

Note: If you are looking for information on the Vincent Thomas Bridge or the Schuyler Heim Bridge, see Route 47.

The SAFETEA-LU act, enacted in August 2005 as the reauthorization of TEA-21, authorized $2,400,000 for High Priority Project #266: Reconstruct the southern terminus off ramps of I-710 in Long Beach. This was noted in the Long Beach Press Telegraph, and actually disappointed Long Beach. The disappointment arose because the bill did not provide funding for a multi-billion project to rebuild the Long Beach Freeway. The city lobbied for $395 million and got nothing. Another $3.2 million was awarded to widen and realign Cherry Avenue from 19th Street to one block south of Pacific Coast Highway. There was $4.8 million set aside for freight transportation management systems, part of $1.3 billion dedicated to freight movement in the state in the new bill. Lastly, there was $100 million to replace the Gerald Desmond Bridge.

Near Route 710, although not originally on Route 710, is the "Gerald Desmond Bridge"*. In August 2005, the SAFETEA-LEU act provided $100 million in funding to replace the Gerald Desmond Bridge.

In February 2010, it was reported that Port of Long Beach officials want to tear down the bridge and replace it with one that is taller and wider to accommodate the biggest cargo ships. Currently, the bridge is so low that some container vessels barely fit under the bridge. Additional problems are the bridge's strategic location as a primary link between Terminal Island cargo facilities and Long Beach (officials at the Los Angeles and Long Beach ports estimate that the bridge carries 15% of all the nation's cargo that moves by sea). The bridge only has five traffic lanes, a walkway on one side, and no shoulders or emergency lanes. Any accident involving vehicles that can't be driven off can shut down one side or the other, diverting traffic onto adjacent streets that are easily jammed.

For years, there was no bridge at all, just a ferry. In 1944, the U.S. Navy erected a pontoon bridge that was supposed to be used for only six months. Instead, the pontoon bridge was in place for 24 years, sometimes with disastrous results. Some motorists, approaching it too fast, became airborne, landed in the water and drowned in their cars. In 1968, the Gerald Desmond Bridge was built, but planners expected only modest traffic -- mostly people going to and from the Long Beach Naval Shipyard on Terminal Island. But by the 1990s, the shipyards were closed and the fishing industry had all but disappeared. Long Beach then emerged as the nation's busiest container port, until 2001, when it was eclipsed by the neighboring port of Los Angeles. Due to the constant pounding of heavy trucks and commuter traffic, its Caltrans structural "sufficiency" rating is only 43 out of a possible 100 points as of August 2007, and the bridge wears nylon mesh "diapers" to catch chunks of concrete falling from its deck.

The plans for the new bridge would add a sixth traffic lane and two

emergency lanes and would clear the water by 200', an increase from 165'.

Rep. Laura Richardson (D-Long Beach) has used her membership on the House

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure to push for more than $375

million in federal funds for the project.

(Source: "Bridge poses a tight squeeze for cargo ships", Los Angeles Times, 2/9/2010)

In late September 2010, the Long Beach City Council approved the $1.1billion port plan to replace the Gerald Desmond Bridge, clearing the way for Long Beach's largest public-works project in decades. Construction was expected to begin sometime in 2011 and take 5 to 6 years. The replacement bridge includes emergency shoulders in each direction, and it expands from four to six the total number of lanes. It will rise more than 50 feet higher than the existing span. The replacement will be constructed just several feet from the existing span, which will remain open throughout construction. The old bridge will then be taken down during a yearlong deconstruction starting in 2015. The bridge replacement project is expected to support about 4,000 jobs annually through 2016. Officials say it could last as long as 100 years, though strict maintenance will be needed to ensure a long life. The cost of the new bridge is estimated at $950 million. Of that, roughly $500 million will come from state highway transportation funds, $300 million from federal sources, $114 million from the Port of Long Beach and $28 million from Los Angeles County Metro.

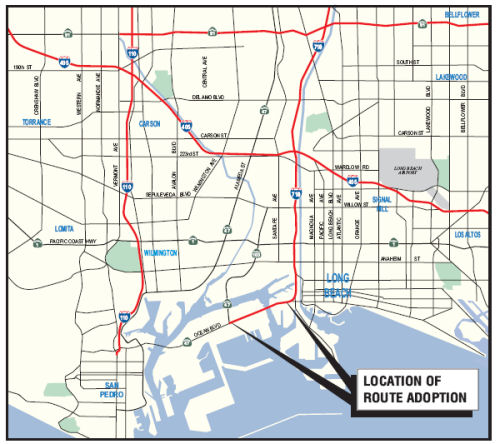

In September 2010, the CTC approved for future

consideration of funding and route adoption a project that will replace

the existing Gerald Desmond Bridge with a new structurally sound bridge

linking Terminal Island and Long Beach/Route 710; provide sufficient

roadway capacity to handle current and projected vehicular traffic volume

demand; and provide sufficient vertical clearance for safe navigation

through the Back Channel to the Inner Harbor. The replacement bridge will

be constructed just north of the existing bridge in order to maintain

access between Terminal Island and the Route 710 during construction. As

part of the project, existing connections to the Route 710 interchange,

and Ocean Boulevard in downtown Long Beach would be replaced, as would the

connector ramps between Route 710 and the bridge. A new hook ramp or loop

ramp would be used to replace the existing on-ramp between Pico Avenue and

the WB Gerald Desmond Bridge. The current ramp between Pico Avenue would

be partially reconstructed to join the new connectors from Route 710. As

part of the Project, the bridge and Ocean Boulevard would become part of

Route 710 and would operate as a freeway facility with controlled access.

The improvements between the existing Route 710 and Route 47, including

the bridge, would be transferred to Caltrans by easement following route

adoption and execution of a freeway agreement. It is estimated that the

transfer would be completed within 2 years after construction. The project

is programmed with TCIF and SHOPP funds. At the time of programming, the

project was estimated to cost $1,125,200,000 and was programmed with

Federal ($318,000,000), TCIF/SHOPP ($250,000,000), Local ($17,300,000),

POLB ($375,100,000) and Port Intermodal Cargo Fees ($164,800,000).

However, according to the POLB, the most recent cost estimate, developed

in January 2010, resulted in a reduced project cost of $950,000,000. The

new estimate reflects recent cost reductions related to the redesign of

some elements, as well as current market conditions. Once a funding plan

is approved for the project by the POLB, the POLB will request an

amendment to the TCIF baseline agreement to reflect the approved funding

plan. The POLB, in coordination with Caltrans, is currently developing a

funding plan based on a design-build delivery method pursuant to Senate

Bill 4, Second Extraordinary Session. The POLB intends to request

design-build approval at a future Commission meeting. The project is

estimated to begin construction in FY 2012/13.

In September 2010, the CTC approved for future

consideration of funding and route adoption a project that will replace

the existing Gerald Desmond Bridge with a new structurally sound bridge

linking Terminal Island and Long Beach/Route 710; provide sufficient

roadway capacity to handle current and projected vehicular traffic volume

demand; and provide sufficient vertical clearance for safe navigation

through the Back Channel to the Inner Harbor. The replacement bridge will

be constructed just north of the existing bridge in order to maintain

access between Terminal Island and the Route 710 during construction. As

part of the project, existing connections to the Route 710 interchange,

and Ocean Boulevard in downtown Long Beach would be replaced, as would the

connector ramps between Route 710 and the bridge. A new hook ramp or loop

ramp would be used to replace the existing on-ramp between Pico Avenue and

the WB Gerald Desmond Bridge. The current ramp between Pico Avenue would

be partially reconstructed to join the new connectors from Route 710. As

part of the Project, the bridge and Ocean Boulevard would become part of

Route 710 and would operate as a freeway facility with controlled access.

The improvements between the existing Route 710 and Route 47, including

the bridge, would be transferred to Caltrans by easement following route

adoption and execution of a freeway agreement. It is estimated that the

transfer would be completed within 2 years after construction. The project

is programmed with TCIF and SHOPP funds. At the time of programming, the

project was estimated to cost $1,125,200,000 and was programmed with

Federal ($318,000,000), TCIF/SHOPP ($250,000,000), Local ($17,300,000),

POLB ($375,100,000) and Port Intermodal Cargo Fees ($164,800,000).

However, according to the POLB, the most recent cost estimate, developed

in January 2010, resulted in a reduced project cost of $950,000,000. The

new estimate reflects recent cost reductions related to the redesign of

some elements, as well as current market conditions. Once a funding plan

is approved for the project by the POLB, the POLB will request an

amendment to the TCIF baseline agreement to reflect the approved funding

plan. The POLB, in coordination with Caltrans, is currently developing a

funding plan based on a design-build delivery method pursuant to Senate

Bill 4, Second Extraordinary Session. The POLB intends to request

design-build approval at a future Commission meeting. The project is

estimated to begin construction in FY 2012/13.

In December 2011, it was reported that the Final Environmental Impact

Report for the new Gerald Desmond Bridge includes a bicycle and pedestrian

walkway. The proposed bike and pedestrian path is one of two revisions to

the draft EIR (the other includes sound mitigation measures for pile

driving and drilling during construction). The EIR includes the following

description of the bike path: “A single, continuous, non-motorized

Class I bikeway (bike path) connecting Route 47 to Pico Avenue. The Class

I bikeway shall be a minimum of 12 feet wide, and signed and striped for

two-way movement. The Class I bikeway shall be located along the south

side of the main span and approach bridges, and shall be essentially the

same elevation as the bridge deck. Protective railings shall be of an open

design that provides and protects public views from the bridge.” The

proposed bike path does not connect to the LA River trail, which, in turn,

connects to Downtown LA, although port planners have already begun to look

for ways to make the connection. At one point, construction on the new

bridge was expected to begin in 2011, but as it turns out, an RFP for a

design-build of the new bridge was sent to four pre-qualified bidders

earlier this fall. The bids are expected in February, with final

contractor selection in March. Design will take 12 to 18 months, and the

bridge is scheduled to open in March 2016.

(Source: Curbed LA, 12/13/11)

In May 2012, it was reported that a joint venture team is the "best value" bidder with a $649.5 million proposal to replace the Gerald Desmond Bridge. Major members of the joint venture team include Shimmick Construction Co. Inc., FCC Construction S.A., Impregilo S.p.A., Arup North America Ltd. and Biggs Cardosa Associates Inc. A decision by the board on the actual award of the contract is expected in late June, with construction to kick off in early 2013. The total cost of the overall bridge replacement project is estimated at about $1 billion.

In September 2012, the CTC updated the project schedule to reflect switching from Design-Bid-Build to Design Build delivery method. In addition, contract negotiations with the winning bidder added time to the schedule, as well as extensive utility relocations, and revalidation of the environmental documents caused by the addition of a Class 1 bicycle path to the project. The new schedule shows construction completion in June 2016 (6 months earlier), with closeout completed in September 2016.

In October 2012, the CTC approved $153,657,000 for bridge construction.

In January 2013, it was reported that ground was broken on the Gerald Desmond Bridge construction. The $1 billion project will replace the aging span with a new structure that will have towers reaching 500 feet above ground level, additional traffic lanes, a higher clearance to accommodate the new generation of cargo ships, dedicated bicycle paths and pedestrian walkways, including scenic overlooks 200 feet above the water, according to the port. The development is expected to create about 3,000 jobs a year between 2013 and 2016, and generate $2billion of regional economic activity, port officials say.

In October 2013, it was reported that crews started clearing the path for

a new Gerald Desmond Bridge encountered a mishmash of old and active oil

wells tangled with 10 miles of utility lines beneath the surface, many of

them unmapped or deeper than expected. The effort to cap and relocate the

dozens of wells and lines turned into months of labor intensive work to

clear the way for large steel-and-concrete piles as deep as an 18-story

building. This raised the bridge's budget by over $200 million. It’s

part of the challenge of building on one of the largest oil fields in the

continental United States. Stretching 13 miles long and 3 miles deep, the

Wilmington Oil Field sprouted with more than 6,000 oil wells in the 1930s,

when oil was discovered beneath the port and the city. The work has

included removing the old casings one section at a time while shoring up

the soil so it doesn’t collapse on the work crews are doing;

handling pipes as deep as 50 feet and injecting liquid nitrogen into the

soil to keep water from flowing into a trench for a utility line

relocation; and filling a 10-foot tall and wide tunnel found near one of

the new bridge’s foundations that once flowed with sea water to cool

a nearby power plant. Completion of the bridge is expected in 2016.

(Source: LA Daily News, 10/6/13)

In November 2013, it was reported that the new bridge (not necessarily

named the Gerald Desmond) will be held upright by an extensive network of

more than 300 steel and concrete support piles, built into the ground as

deep as an 18-story building. To make room, port officials have directed a

two-year blitz to remove or cap dozens of oil wells and dig up miles of

utility lines that lie beneath the bridge's footprint. The work involves

removing oil well casings as deep as 200 feet, section by section.

Engineers designed custom tools to cut the steel pipes from inside and

out, all while operating within a 7-foot-diameter drum to stabilize the

surrounding soil. Once the casings are removed, the void is filled with a

soil-like mixture of sand and mud. Further complicating the operation is

that parts of the area sank as much as 30 feet in the 1940s and 1950s, the

result of a boom on one of the nation's largest oil fields. Years later,

soil was spread over the sunken landscape and new utility lines

crisscrossed those buried under the new fill. Many of them were identified

only with rough maps that pre-dated the precision of GPS, meaning crews

had to employ guesswork when navigating the maze of pipes, tunnels and

wires.

(Source: Los Angeles Times, 11/16/13)

In June 2014, it was reported that the massive $1.26 billion project to

replace the ailing Gerald Desmond Bridge in Long Beach will be delayed at

least a year, pushing back the opening and completion from the end of

2016, to late 2017 or early 2018. The delay has been attributed to design

issues, including delays in obtaining approval for designs from Caltrans

officials, who have the ultimate authority over plans. The operation has

already been plagued with complications and cost overruns from a maze of

poorly mapped underground utility lines and oil wells on Terminal Island.

(Source: Los Angeles Times, 6/27/14)

In October 2016, the CTC authorized an additional $57,166,000 in State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP) funds for this project: $24,206,000 in additional funds for construction support and $32,960,000 for construction capital. This project will replace the Port of Long Beach owned Gerald Desmond Bridge with a new cable-stayed bridge that will be incorporated into the State Highway System when completed. The existing bridge accommodates approximately 10 percent of all U.S. waterborne container volume, via the trucking of containers between the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles and the inland warehousing, transloading and distribution centers. This bridge is vital to the Southern California and State economies and it is a nationally important transportation asset. As the future owner-operator of the new bridge, the Department has critical interest and compelling responsibility to ensure that the new bridge is designed and constructed to be durable, resilient and able to withstand seismic events. The overall project cost for the Port’s project has increased over 50 percent from $950 million in 2010 to approximately $1.5 billion today. The Department’s $57,166,000 increase is approximately 10 percent of the total cost increase of $541,901,000 ($1,491,901,000 - $950,000,000). In early 2013, the Department had concerns with the design-builder’s proposed design with regards to long-term durability and potential for failure of the hollow towers supporting the main span during a seismic event. It is a well-established design practice on highway bridges to limit the permanent axial load ratio to no more than 15 percent to achieve seismic design criteria ductility requirements. Caltrans seismic standards, and the primary national seismic standards and guidance are based on laboratory testing consistent with axial loads in this range. The design-builder’s proposed tower cross-section design resulted in axial load ratio ranges from 24 percent to 34 percent. An in-depth review of hollow column research and details of other California bridges supported on hollow towers confirmed that the proposed axial load range and column aspect ratios were unprecedented in the tower design and were based upon mathematical models that had not been validated through any known seismic testing. After consultation with internationally recognized seismic research experts and independent evaluations and analysis by Caltrans in-house experts and the Port’s consulting engineer, the recommendation to redesign the tower was presented to the Caltrans Directorate. After lengthy internal discussions, involving the State Bridge Engineer, the Chief Engineer, the Director, consult with the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), as well as discussions between the Department, the Port and the design-builder, both partners finally agreed to require the design-builder to redesign the tower with a lower axial load ratio with an acceptable level of ductility to ensure seismic safety and the long term structural integrity of the bridge. The Department estimates the tower redesign cost at $63,293,000, and hired an independent estimator to validate this number. The Department’s initial contribution of $500,000,000 was 52.07 percent of the original project budget of $950,000,000. Using the original State contribution percentage, the Department is requesting 52.07 percent cost share of $63,293,000, totaling $32,960,000 in additional SHOPP funding for construction capital. This project was originally scheduled to open for use in under 4 years, meaning it would be open for traffic by now under the original schedule. Challenges encountered during the design and construction delayed the bridge completion. The design-builder’s current schedule for completion has been delayed two-and-one-half years, with further delays possible. The lengthiest schedule delays are due to the Bent 15 Foundation (the structure that anchors the cable) redesign due to differing site condition and the tower redesign.

In December 2017, it was reported that state, local and federal officials

joined construction crews for a “topping out” ceremony to

celebrate the completion of the two 515-foot-tall towers for the new Port

of Long Beach bridge, Port of Long Beach reports. The towers will be the

centerpieces of California’s first cable-stayed bridge for vehicular

traffic, which will be one of the tallest of its kind in the nation. In

addition to the completion of the towers, stretches of the new

bridge’s westbound lanes have been completed and construction of the

eastbound lanes has began. The new bridge will include six traffic lanes

and four emergency shoulders, a higher clearance to accommodate large

cargo ships, more efficient transition ramps and connectors to improve

traffic flow, and a bike and pedestrian path with scenic overlooks. The

$1.47 billion bridge project, which is expected to be completed in 2019,

is a joint effort between Caltrans and the Port of Long Beach, with

additional funding from the U.S. Department of Transportation and the Los

Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The replacement

project enables the Gerald Desmond Bridge to remain in use while the new

bridge is under construction.

(Source: Equipment World, 12/13/2017)

In July 2018, it was reported that several large excavators equipped with

jackhammers and claws tore down the elevated ramp that connects eastbound

Ocean Boulevard to northbound I-710. The demolition marks the project's

final long-term road closure. Eastbound traffic leaving Terminal Island

and San Pedro to northbound I-710 will use the new bridge when the new

bridge is complete.

(Source: NBC LA 7/5/2018)

In December 2018, it was reported that one of the two Pico Ave offramps

(~ LA 5.215) from the current I-701 EB was being closed permanently.

Eastbound traffic coming off the Gerald Desmond has been funneled onto

Pico Avenue to get around the construction site. That still will be the

case, but now there will be only one offramp from Pico Avenue. The other

offramp is being closed permanently to clear space for bridge

construction. Drivers still can get to I-710 or Ocean Boulevard going to

downtown Long Beach from Pico Avenue. As motorists leave the bridge, those

going north to I-710 should stay in the left lanes while traffic to

downtown should stay in the right lane.

(Source: Long Beach Press Telegram, 11/29/2018)

In July 2019, it was reported that an innovative traffic

feature of the new bridge under construction at the Port of Long Beach is

scheduled to open early on Saturday, July 20, 2019 enabling trucks and

other vehicles to make a safe and free-flowing U-turn at the west end of

the project. The “port access undercrossing” is a second

tunnel near the intersection of Ocean Boulevard and Route 47 on Terminal

Island. This “Texas U-turn,” so named because it’s a

common feature at intersections in the Lone Star state, enables vehicles

traveling on one side of a one-way frontage road to make a U-turn onto the

opposite frontage road without stopping at a traffic signal. Detour

for traffic on Pier T Avenue. With the opening of the new undercrossing,

trucks and other vehicles leaving the Pier T complex and heading east over

the existing bridge to reach the northbound I-710 Freeway will now take a

new route. Starting at 10 p.m. on Friday, July 19, construction crews will

permanently close the eastbound Ocean Boulevard loop onramp from Pier T

Avenue on Terminal Island. The closure is needed so crews can build new

roadways on the south side of Ocean Boulevard. The detour for all vehicles

headed east will take vehicles to the port access undercrossing. When

fully completed, the new cable-stayed bridge will include six traffic

lanes and four emergency shoulders, a higher clearance to accommodate

large cargo ships, a bike and pedestrian path with scenic overlooks, and

more efficient transition ramps and connectors to improve traffic flow.

In July 2019, it was reported that an innovative traffic

feature of the new bridge under construction at the Port of Long Beach is

scheduled to open early on Saturday, July 20, 2019 enabling trucks and

other vehicles to make a safe and free-flowing U-turn at the west end of

the project. The “port access undercrossing” is a second

tunnel near the intersection of Ocean Boulevard and Route 47 on Terminal

Island. This “Texas U-turn,” so named because it’s a

common feature at intersections in the Lone Star state, enables vehicles

traveling on one side of a one-way frontage road to make a U-turn onto the

opposite frontage road without stopping at a traffic signal. Detour

for traffic on Pier T Avenue. With the opening of the new undercrossing,

trucks and other vehicles leaving the Pier T complex and heading east over

the existing bridge to reach the northbound I-710 Freeway will now take a

new route. Starting at 10 p.m. on Friday, July 19, construction crews will

permanently close the eastbound Ocean Boulevard loop onramp from Pier T

Avenue on Terminal Island. The closure is needed so crews can build new

roadways on the south side of Ocean Boulevard. The detour for all vehicles

headed east will take vehicles to the port access undercrossing. When

fully completed, the new cable-stayed bridge will include six traffic

lanes and four emergency shoulders, a higher clearance to accommodate

large cargo ships, a bike and pedestrian path with scenic overlooks, and

more efficient transition ramps and connectors to improve traffic flow.

(Source: AJOT, 7/17/2019)

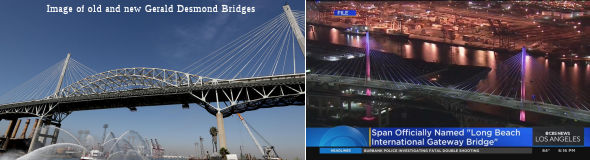

In October 2020, the new Gerald Desmond Bridge opened for traffic. The

following are some relevant statistics / pieces of information about the

new bridge:

(Source: Los Angeles Times, 10/2/2020, We Build Value Magazine, 8/29/2020)

In February 2022, it was reported that demolition on the old Gerald

Desmond Bridge is set to begin in May 2022. The old bridge opened in 1968

and is named after a former Long Beach city attorney who helped secure

funding to build the 5,134-foot-long span. It was decommissioned in

October 2020 when its replacement, also called the Gerald Desmond Bridge,

opened. Demolition operations on the old bridge will start with the

dismantling and removal of the main span — an operation that will

shut down the port’s Back Channel, a canal that runs under the

bridge, for a weekend. During that time, the old bridge’s main span

will be disconnected and lowered onto a barge. Full demolition is expected

to be concluded by the end of 2023. Demolition will cost $59.9 million,

which was included in the overall $1.47-billion budget used to build the

new bridge. The port awarded a contract in July 2021 to Kiewit West Inc.

to dismantle and remove main steel truss spans, steel plate girder

approaches, abutments, columns, access ramps, foundations and other pieces

of the old bridge. Metal and other materials removed from the old bridge

will be hauled to a recycling site for salvaging and reuse.

(Source: LA Times, 2/26/2022)

Demolition actually began in July 2022. During the last years of its use,

the original span carried around 68,000 California vehicles daily.

Demolition began with the operation to remove the suspended main span

section on the Back Channel, requiring a 48-hour closure of the channel to

all boat traffic. The plan is for the 125m-long span to be dismantled, cut

and lowered onto a barge. Dismantling and removal of the main spans, steel

trusses, steel plate connections, columns and access ramps will take until

the end of 2023. Funding for the nearly US$60 million demolition project

is included within the overall $1.57 billion budget that was allocated to

design and build the replacement bridge. The old bridge’s main span

was disconnected from the rest of the bridge and has been slowly lowered

the 50m in one piece to be placed onto a barge in the water.

(Source: World Highways, 7/14/2022)

In August 2023, the CTC approved a request for an additional $49,600,000 in Construction Capital for the SHOPP Bridge Rehabilitation and Replacement project on I-710 in Los Angeles County, to close out the construction contract. This project is located on I-710, in the City of Long Beach, near the Port of Long Beach (Port), at the Gerald Desmond Bridge № 53-3000, in Los Angeles County. The project (07-LA-710 3.7/6, PPNO 07-3037, ProjID 0700000379; EA 22830) replaced the bridge and is now named the Long Beach International Gateway Bridge. The project is funded through a combination of Federal, State, and Port sources. The original cost estimate, in July 2008, was based on a 30 percent level of design development of $950,000,000. In June 2011, this project was allocated $433,602,000 in Construction Capital and $66,398,000 Support in the SHOPP. In October 2012, the project was amended to revise $153,657,000 in Construction Capital in the SHOPP to Proposition 1B Corridor Mobility Improvement Account. In October 2016, the project received supplemental funds in the amount of $32,960,000 in Construction Capital and $15,000,000 in Construction Support. In March 2018, the project received supplemental funds in the amount of $19,206,000 in Construction Support. There are no remaining funds in Construction Capital. The project is 100 percent complete, and Construction Contract Acceptance was in February 2022, however additional funding is needed related to claims submitted by the contractor and settled by the Port. The requested amount represents the Department’s share of the settlement of all outstanding claims that were filed by the contractor and settled by the Port. The Port is the administrator of the contract, and the Department is a funding partner for the project. Construction began in October 2012, opened to traffic in October 2020, construction completed in December 2020, and the new bridge was transferred to the Department in March 2022. The Port issued 107 change orders during the design-build process resolving some disputes encountered during construction. However, a number of outstanding claims for extra work and time-related costs in excess of $250,000,000 remained unresolved as the project neared completion. The Department helped the Port by carefully examining the claims, and they found that the amount of $130,000,000 was reasonable. As a result, the Port went on to settle these claims with the contractor for that specific amount.

Route 710: Port of Los Angeles and Long Beach

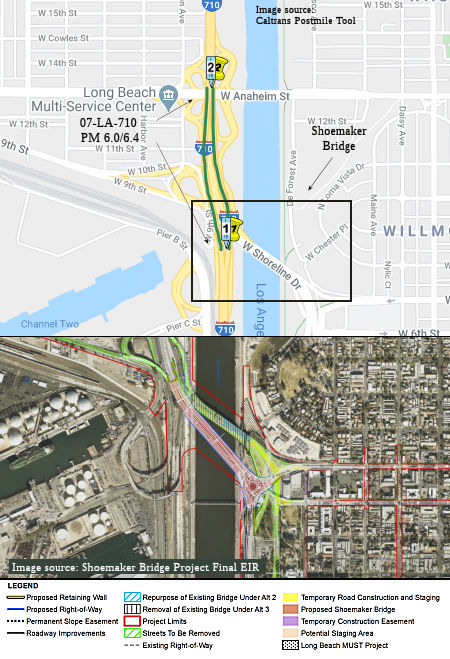

Shoemaker Bridge Replacement (07-LA-710 PM 6.0/6.4)

The 2018 STIP, approved at the CTC March 2018 meeting, appears to allocate $14,000K in Advance Project Development Element funds for PPNO 4071, Rt 710 S.Early

Action-replace Shoemaker Br (LA 6.402).

The 2018 STIP, approved at the CTC March 2018 meeting, appears to allocate $14,000K in Advance Project Development Element funds for PPNO 4071, Rt 710 S.Early

Action-replace Shoemaker Br (LA 6.402).

In August 2020, the CTC approved for future

consideration of funding 07-LA-710 PM 6.0/6.4 – Los Angeles

County Shoemaker Bridge Replacement Project. Replace bridge and

other improvements. (FEIR) (PPNO 4071) (EA 27300) (STIP). The Project will

replace the Shoemaker Bridge and add pedestrian, bicycle, and other street

enhancements. The project is located in the southern end of Route 710 in

the City of Long Beach. On April 21, 2020, the Long Beach City Council

adopted a Mitigated Negative Declaration for the Project and found that

the Project would not have a significant effect on the environment after

mitigation. The Project is estimated to cost $30,700,000 and is funded

through design with State Transportation Improvement Program Funds

($14,000,000) and Measure R Funds ($16,700,000). Construction is estimated

to begin in Fiscal Year 2022-23.

(Source: June 2020 CTC Agenda, Agenda Item

2.2c.(12); August 2020 CTC Agenda, Agenda Item 2.2c.(5); August 2020 CTC

Agenda, Agenda Item 2.5c.(5))

According to the City of Long Beach, the project

proposes to replace the Shoemaker Bridge (West Shoreline Drive) in the

City of Long Beach, California. The Shoemaker Bridge Replacement Project

(proposed project) is an Early Action Project of the I-710 Corridor

Improvement Project and is located at the southern end of I-710 in the

City of Long Beach and is bisected by the Los Angeles River. The purpose

of the proposed project is to improve existing traffic safety and

operations; increase multi-modal connectivity within the project limits

and surrounding area; enhance Complete Streets elements by providing

bicycle, pedestrian, and streetscape improvements on major thoroughfares;

and, address non-standard features and design deficiencies. Three

Alternatives are being evaluated as part of the proposed project:

(Source: Shoemaker Bridge Project Page; Shoemaker Bridge Environmental Impact Report/Environmental Assessment)

Alternatives 2 and 3 will include the evaluation of

design options for a roundabout or a “Y” intersection at the

easterly end of the bridge. The Build Alternatives would include bicycle

and pedestrian uses along the south side of the new bridge and also

provide improvements along associated roadway connectors to downtown Long

Beach, West Shoreline Drive from I-710, and portions of 3rd Street, 6th

Street, 7th Street, and West Broadway from Cesar E. Chavez Park to

Magnolia Avenue. The proposed improvements may include additional street

lighting, restriping, turn lanes, bicycle, pedestrian, and streetscape

improvements. Additionally, the Build Alternatives evaluate the impacts

from the closure of the 9th and 10th Street ramp connections into downtown

Long Beach.

(Source: Shoemaker Bridge Project Page; Shoemaker Bridge Environmental Impact Report/Environmental Assessment)

The Preferred Alternative, Alternative 3 (Design Option

A), includes the complete removal of the existing Shoemaker bridge and

construction of the new bridge with a roundabout on the eastern end of the

proposed bridge. Local road improvements would occur throughout the

Project limits including those on West Shoreline Drive, West 3rd Street,

Ocean Boulevard, Golden Shore/Golden Avenue, West Seaside Avenue, West

Broadway, West 6th Street, West 7th Street, West 9th Street, West 10th

Street, and Anaheim Street. The new Shoemaker Bridge would consist of

multiple structures, with spans that cross the LA River, the northbound

(NB) lanes of Route 710, and the LA River and Rio Hondo (LARIO) Trail. The

new ramps would be located approximately 500 feet (measured from

centerline) south of the existing Shoemaker Bridge.

(Source: Shoemaker Bridge Project Page; Shoemaker Bridge Environmental Impact Report/Environmental Assessment)

As of the time of the initiation of the project,

Shoemaker Bridge is under jurisdiction of the City of Long Beach and

serves as the extension of West Shoreline Drive within downtown Long Beach

to the I-710 corridor. I-710 transitions into Route 710 south of Pacific

Coast Highway. Since the existing Shoemaker Bridge is within City

right-of-way (ROW), the City serves as the lead agency under the

CEQA. However, since the new Shoemaker Bridge would require federal

funding and would be transferred to Caltrans for future ownership and

maintenance, Caltrans serves as a Responsible Agency under CEQA as well as

the lead agency under NEPA. The proposed Project is a stand-alone project

that proposes to address design and safety deficiencies associated with

the existing Shoemaker Bridge and improve circulation and

connectivity within downtown Long Beach. Even though the Project is a

stand-alone project, its design would accommodate the future construction

of the I-710 Corridor Project.

(Source: Shoemaker Bridge Project Page; Shoemaker Bridge Environmental Impact Report/Environmental Assessment)

In December 2023, it was reported that plans are being

released for a new $900 million bridge that is slated to replace the aging

Shoemaker Bridge and add 5.6 acres of park space to downtown Long Beach,

something the city hopes to complete by 2028. The new renderings show a

modern cable-stayed bridge with 240-foot tall angled arches that meet in

the middle of the 765-foot-wide bridge. Building the new structure is part

of a plan to realign Shoreline Drive, which would significantly change how

drivers enter and exit the I-710 Freeway. The current plans have cars

using a new roundabout that will circulate traffic onto the bridge, I-710

or city streets. Some other proposed features include a protected bike

lane that would connect Fashion Avenue to the Los Angeles River bike path

on the east side of the river as well as a pedestrian observation point on

the south side of the bridge that looks toward Downtown. The design shown

to the public has not been finalized. Long Beach received a $30 million

federal grant earlier this year for the realignment portion of the project

that will add northbound lanes alongside Shoreline Drive’s current

southbound lanes and eliminate the separate northbound section that has

left an unusable patch of green space west of Cesar E. Chavez Park for

decades. The city has estimated that part of the project will cost about

$60 million. Designs for the Shoreline Drive realignment are expected to

be completed in the spring with construction on the project expected to

start sometime in 2024 or 2025. The new bridge, which is expected to be

built just south of the existing Shoemaker Bridge, would be completed

before the old one is demolished to allow traffic to continue to enter and

exit Downtown during construction. The work will be completed in phases

with some of the park improvements projected to be among the last things

crews finish. The end result would connect Chavez Park to Drake Park,

which is north of Seventh Street. Once the bridge is complete, the Sixth

Street exit will be eliminated and Seventh Street will become a two-way

street to allow traffic to enter and exit I-710 through the new

roundabout. The bridge’s design is expected to allow more movement

for wildlife living in the river below because it will have fewer piers in

its base. The design is also expected to be able to withstand seismic

activity and sea level rise, according to the city.

(Source: Long Beach Post, 12/9/2023)

West Shoreline Drive

Note that West Shortline Drive, beyond the Shoemaker Bridge, is not part of the state highway system, but is maintained by the City of Long Beach. It serves as an extended off-ramp from I-710 into Long Beach.

The SAFETEA-LU act, enacted in August 2005 as the reauthorization of TEA-21, authorized $1,600,000 for High Priority Project #701: Develop and implement traffic calming measures for traffic exiting I-710 into Long Beach.

In February 2023, it was reported that the city of Long

Beach will receive $30 million to support redesign of West Shoreline

Drive, much of which is basically an extended I-710 off-ramp and currently

a major barrier and a safety hazard for local residents. That project will

reconfigure West Shoreline Drive, converting it to a landscaped local

roadway. Lanes will be consolidated, local Cesar Chavez Park will be

doubled in size, and traffic will be moved further away from two nearby

elementary schools. The changes will help create better, safer access

between nearby neighborhoods and community park space, Downtown Long

Beach, and other destinations. The funding is part of the Reconnecting

Communities Pilot program through the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The other cities receiving funds are Oakland, San Jose, Pasadena and

Fresno. The pilot program was established in the nation's Bipartisan

Infrastructure Law, which passed in 2021. Specifically, the grant includes

• Demolition of the existing northbound lane of Shoreline Drive;

• Relocation of major utilities; • Required temporary traffic

control and rerouting; • Major civil engineering and required

regrading; • Removal of old fences, hardscaping, and landscaping;

• Installation of new fiber, irrigation, and power conduits; •

Relocation of street lighting to accommodate new street and park

alignment; • Partial funding for the realigned roadway and new

medians at Shoreline Drive.

(Source: Streetsblog LA, 2/28/2023; Random Lengths News, 2/27/2023)

710 Corridor Mobility Improvements