Click here for a key to the symbols used. An explanation of acronyms may be found at the bottom of the page.

Routing

Routing Post 1964 Signage History

Post 1964 Signage HistoryThe definition of this route is unchanged from 1963.

With respect to the San Fernando Valley portion of the route, Scott

Parker on AARoads noted that there were always two overriding issues with

the SF Valley section of Route 64: one being the billions of dollars

of property acquisition required to deploy a freeway there. But the

second was the presence of Van Nuys Airport, which, along with its

takeoff/landing zone, occupies about two-thirds of the valley's N-S

width. Even though the projected (but never adopted) route

essentially followed Roscoe Blvd., which skirts the north end of the

runway (along with the Metrolink/former SP Santa Susana line), any

facility would have had to be sunk below grade to avoid interference with

airport operations. The Van Nuys Airport (VNY) is one of the

most heavily-used "noncommercial" airfields in the country (no scheduled

passenger flights, but a boatload of private jets), with a runway capable

of handling commercial jets. Anything that would disrupt airfield

operations would never be tolerated; it took decades to get the Roscoe

Blvd. RR overpass through the developmental process; and even then the

vertical apex of the bridge had to be moved about a quarter-mile west so

as to be out of the runway's path.

(Source: Scott Parker (SParker) on AARoads, "Re: Unbuilt CA 64 on the Malibu Canyon-Whitnall Freeway", 4/18/2020)

Pre 1964 Signage History

Pre 1964 Signage HistoryNote: For the proposed extension of US 64 into California, see the page for US 466.

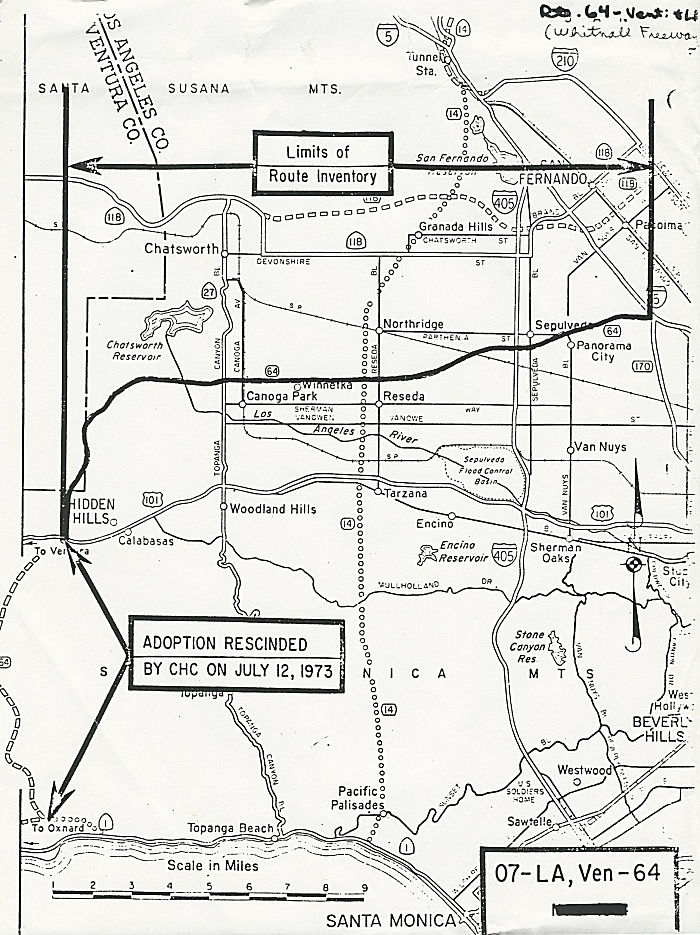

In 1963, it was reported that studies were underway on the Malibu-Whitnall Freeway, anticipating adoption after public hearings sometime in 1964.

Before 1964, the route allocated to the unconstructed post-1964 Route 64

routing was LRN 265 (defined in 1959). This routing ran from the junction

of I-5 and Route 170 across the valley, and then down across Malibu

Canyon. In 1970 Malibu residents, citing ecological and economic concerns,

were able to have 7.5 miles of the proposed freeway deleted from the

master plan. Due to budget cuts and new environmental restrictions,

Whitnall Freeway fell years behind schedule. In parts of the valley

homeowners protested that their frozen property in the right-of-way area

had stuck them in a permanent limbo as they waited for the government to

proceed. Four different attempts were made by valley assemblymen to

eliminate the freeway from the master plan. In 1975 plans for the Whitnall

Freeway were finally abandoned by Caltrans, and the state held a huge

sale, selling the roughly 10 million dollars worth of land it had

accumulated in preparation for the freeway's construction.

(Source: KCET Lost Landmarks, 6/28/2013)

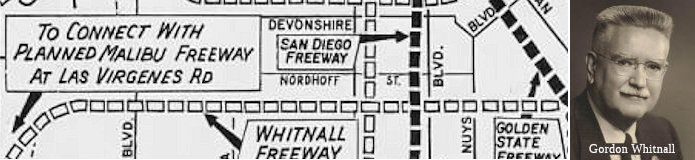

Whitnall Parkway (1927-1934)

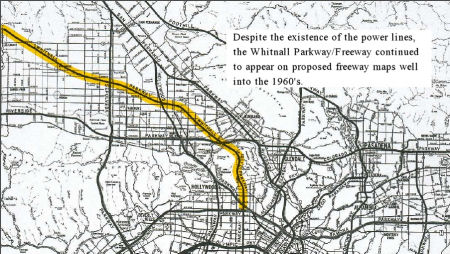

There is a lot of confusion

between the proposal for the Whitnall Freeway (which was Route 64), and an earlier, 1927 proposal for a Whitnall Parkway that

remained on planning maps until the 1960s. The figure to the right shows

the Whitnall Parkway approach; a 2014 LA Times article used words that

made this appear to be the freeway proposal from the 1960s (it clearly

isn't, as the Route 64 freeway ran across Chase and Malibu Canyon, and the

Route 258 freeway ran along Normandie). This approach connects to Route 258, along what is now "Whitnall Highway" in Burbank (which could be the

source of the naming of this route). It does not appear substantiated in

the route definitions, so this doesn't appear to be a highway at the state

level. Gordon Whitnall was involved in city planning around 1916.

Whitnall's vision for Los Angeles was both practical and idealistic. He

believed that Los Angeles' geographical location made it predestined to be

the most important city in the West. He also saw that Los Angeles was not

just L.A. proper, but the numerous other satellite cities that surrounded

it. These contiguous cities suffered from poor transportation and

scattered administrative centers. Quickly promoted to Director of City and

County Planning, he envisioned a sprawling metropolis made up of numerous

organic civic districts, linked together by a series of arterial highways,

and unified by a centrally located administrative and government center

downtown near the historic Plaza, where it would be "accessible to all."

Whitnall and the planning committee also envisioned four "highways" that

would radiate from the valley into arteries leading to the city. These

parkway/highways were more modest in design from the modern freeway, and

often featured a landscaped center strip separating opposing lanes of

traffic. They were Balboa Boulevard, San Fernando Boulevard, Remsen

Boulevard (seemingly never built), and most ambitious of all -- Whitnall

Highway. Whitnall Highway would stretch diagonally southeast by northwest

from Newhall (now part of Santa Clarita) through the San Fernando Valley,

and meet up with the entrance of a two-mile tunnel originating off

Riverside Drive (which was being expanded into a major artery linking the

valley to downtown) that would run under Griffith Park into Hollywood, via

Bronson Avenue. Had this tunnel been built it would be the longest highway

tunnel in California, and even today would rank as the third longest

highway tunnel in the USA. On June 5, 1927, the first section of Whitnall

Highway opened to a crowd of 300 at the intersection of Whitnall and

Cahuenga Boulevard. Gordon, the guest of honor, christened the highway at

the ceremony, which also celebrated the opening of 400 residential tracts

owned by the Hugh Evans Corporation. Homeowners in the projected path of

the highway began to protest the city's attempt to enforce its right of

way through their property. The road was extended, despite further

protests, to Oxnard Boulevard in 1931. Yet, after 1934, both plans for the

highway and the tunnel abruptly disappeared from the news, though

variations continued to appear on maps of proposed transit routes. Over

the years, Burbank and North Hollywood tried to figure out what to do with

the quirky wide road, and all the free public space below the giant

transmission towers which loomed overhead. Portions of the land were used

as makeshift playgrounds, parks, and bike trails, but by 1973 the city of

Burbank was at a loss. The community seemed to have little interest in

pushing for landscaping, or the creation of public parks, and the city had

a hard time commercially leasing the land, since nothing permanent could

be built under the structures. In 1989 a group of mentally challenged

people created a garden on 21 miles under the power lines. In the '90s

Burbank finally commissioned the Whitnall Highway Parks North and South.

There is a lot of confusion

between the proposal for the Whitnall Freeway (which was Route 64), and an earlier, 1927 proposal for a Whitnall Parkway that

remained on planning maps until the 1960s. The figure to the right shows

the Whitnall Parkway approach; a 2014 LA Times article used words that

made this appear to be the freeway proposal from the 1960s (it clearly

isn't, as the Route 64 freeway ran across Chase and Malibu Canyon, and the

Route 258 freeway ran along Normandie). This approach connects to Route 258, along what is now "Whitnall Highway" in Burbank (which could be the

source of the naming of this route). It does not appear substantiated in

the route definitions, so this doesn't appear to be a highway at the state

level. Gordon Whitnall was involved in city planning around 1916.

Whitnall's vision for Los Angeles was both practical and idealistic. He

believed that Los Angeles' geographical location made it predestined to be

the most important city in the West. He also saw that Los Angeles was not

just L.A. proper, but the numerous other satellite cities that surrounded

it. These contiguous cities suffered from poor transportation and

scattered administrative centers. Quickly promoted to Director of City and

County Planning, he envisioned a sprawling metropolis made up of numerous

organic civic districts, linked together by a series of arterial highways,

and unified by a centrally located administrative and government center

downtown near the historic Plaza, where it would be "accessible to all."

Whitnall and the planning committee also envisioned four "highways" that

would radiate from the valley into arteries leading to the city. These

parkway/highways were more modest in design from the modern freeway, and

often featured a landscaped center strip separating opposing lanes of

traffic. They were Balboa Boulevard, San Fernando Boulevard, Remsen

Boulevard (seemingly never built), and most ambitious of all -- Whitnall

Highway. Whitnall Highway would stretch diagonally southeast by northwest

from Newhall (now part of Santa Clarita) through the San Fernando Valley,

and meet up with the entrance of a two-mile tunnel originating off

Riverside Drive (which was being expanded into a major artery linking the

valley to downtown) that would run under Griffith Park into Hollywood, via

Bronson Avenue. Had this tunnel been built it would be the longest highway

tunnel in California, and even today would rank as the third longest

highway tunnel in the USA. On June 5, 1927, the first section of Whitnall

Highway opened to a crowd of 300 at the intersection of Whitnall and

Cahuenga Boulevard. Gordon, the guest of honor, christened the highway at

the ceremony, which also celebrated the opening of 400 residential tracts

owned by the Hugh Evans Corporation. Homeowners in the projected path of

the highway began to protest the city's attempt to enforce its right of

way through their property. The road was extended, despite further

protests, to Oxnard Boulevard in 1931. Yet, after 1934, both plans for the

highway and the tunnel abruptly disappeared from the news, though

variations continued to appear on maps of proposed transit routes. Over

the years, Burbank and North Hollywood tried to figure out what to do with

the quirky wide road, and all the free public space below the giant

transmission towers which loomed overhead. Portions of the land were used

as makeshift playgrounds, parks, and bike trails, but by 1973 the city of

Burbank was at a loss. The community seemed to have little interest in

pushing for landscaping, or the creation of public parks, and the city had

a hard time commercially leasing the land, since nothing permanent could

be built under the structures. In 1989 a group of mentally challenged

people created a garden on 21 miles under the power lines. In the '90s

Burbank finally commissioned the Whitnall Highway Parks North and South.

(Source: LA Times, 10/28/2014; KCETLost

Landmarks, 6/28/2013; Jayne Vidheecharoen/Slideshare, 4/18/2011)

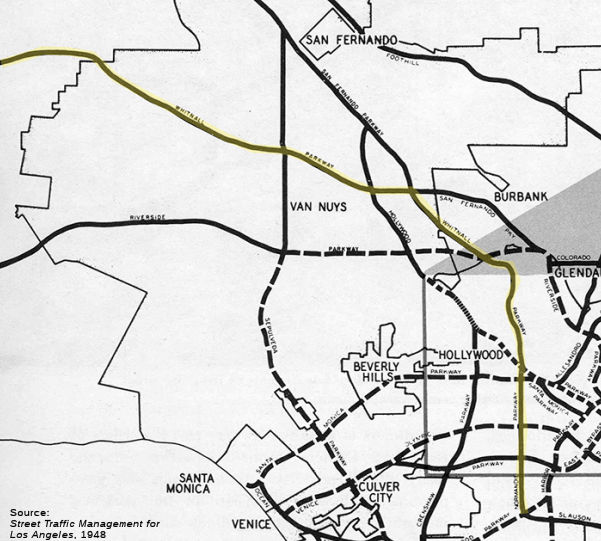

A late 1940s parkway plan shows the Whitnall Parkway in a bit more detail.

This image, from the 1948 publication Street Traffic Management for Los Angeles, shows the freeway / parkway plan that had been in the works during the 1940s (at least from

the city's perspective). It had the Whitnall Parkway following much of the

rail line across the San Fernando Valley and seemingly into Simi Valley.

At the Southeastern end, the Whitnall Parkway connected to the Normandie

Parkway (which provides some explanation for why Route 258 was also

considered part of the Whitnall Freeway).

A late 1940s parkway plan shows the Whitnall Parkway in a bit more detail.

This image, from the 1948 publication Street Traffic Management for Los Angeles, shows the freeway / parkway plan that had been in the works during the 1940s (at least from

the city's perspective). It had the Whitnall Parkway following much of the

rail line across the San Fernando Valley and seemingly into Simi Valley.

At the Southeastern end, the Whitnall Parkway connected to the Normandie

Parkway (which provides some explanation for why Route 258 was also

considered part of the Whitnall Freeway).

(Source: LA Metro Primary Resources, "Past Visions of Los Angeles’ Transportation Future: 1940s", retrieved 12/23/2023)

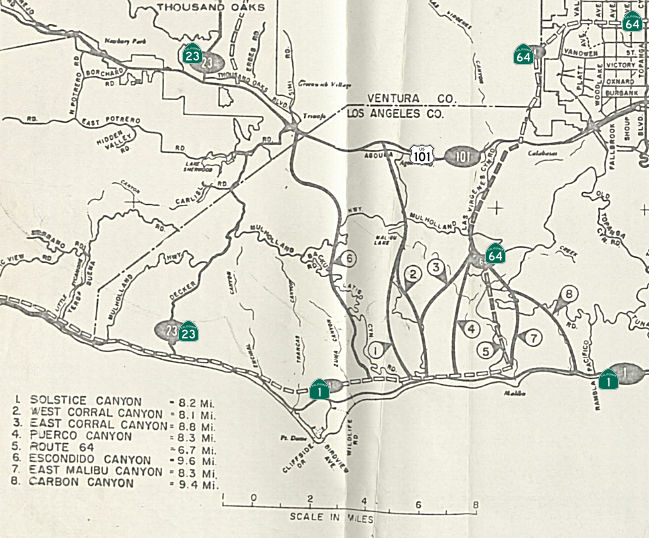

The Route 64

Malibu-Whitnall Freeway plans were laid out in 1963. Originally, Decker

Canyon had been selected for the project in 1958, but Malibu Canyon

replaced it. Route 64 would have connected the Pacific Coast Highway with

US 101, traveling north via Malibu Creek. The route would have then

extended north and swung east to eventually meet Route 170 and I-5,

traversing Van Nuys. The Valley part of the route changed after the Route 118 Freeway plans were finalized. Freeway’s supporters

included most of the Valley’s Chambers of Commerce, the San Fernando

Valley Industrial Association, and Malibu land companies. The

supporters’ major concerns were overcrowded coastal highways and

taxpayers’ lack of access to the beach. Malibu residents wanted

their ingress and egress. The opposition consisted of residents from both

Malibu and the Valley, the Sierra Club, the Save Malibu Canyon Committee,

and the environment minded. The opposers critiqued the drive to construct,

coining then Governor Reagan’s phrase “the bulldozer mentality

of the past”, and fought for preservation, reiterating the severe

and irreversible damage on ecology and wildlife if crews blocked the water

stream and disfigured the mountainous terrain. There would have been

interchanges in the Malibu portion at Route 1, Malibu Canyon Road, Cold

Canyon/Piuma Road, Mulholland Highway, Lost Hills Road, and US 101. The

route would have run just to the E of existing Las Virgenes/Malibu Canyon

Road. The project hit pause in 1970 when the need for this freeway was

repeatedly questioned. Authority was deferred to county and State

Department of Parks and Recreation officials to determine how to best use

Malibu’s land. Factors for halting Route 64 included the high cost

for property acquisition, on top of the high costs of constructing tunnels

and excavating in Malibu’s mountainous terrain, the position of the

Van Nuys Airport, which the freeway had to cross, and persistent

ecological concerns.

The Route 64

Malibu-Whitnall Freeway plans were laid out in 1963. Originally, Decker

Canyon had been selected for the project in 1958, but Malibu Canyon

replaced it. Route 64 would have connected the Pacific Coast Highway with

US 101, traveling north via Malibu Creek. The route would have then

extended north and swung east to eventually meet Route 170 and I-5,

traversing Van Nuys. The Valley part of the route changed after the Route 118 Freeway plans were finalized. Freeway’s supporters

included most of the Valley’s Chambers of Commerce, the San Fernando

Valley Industrial Association, and Malibu land companies. The

supporters’ major concerns were overcrowded coastal highways and

taxpayers’ lack of access to the beach. Malibu residents wanted

their ingress and egress. The opposition consisted of residents from both

Malibu and the Valley, the Sierra Club, the Save Malibu Canyon Committee,

and the environment minded. The opposers critiqued the drive to construct,

coining then Governor Reagan’s phrase “the bulldozer mentality

of the past”, and fought for preservation, reiterating the severe

and irreversible damage on ecology and wildlife if crews blocked the water

stream and disfigured the mountainous terrain. There would have been

interchanges in the Malibu portion at Route 1, Malibu Canyon Road, Cold

Canyon/Piuma Road, Mulholland Highway, Lost Hills Road, and US 101. The

route would have run just to the E of existing Las Virgenes/Malibu Canyon

Road. The project hit pause in 1970 when the need for this freeway was

repeatedly questioned. Authority was deferred to county and State

Department of Parks and Recreation officials to determine how to best use

Malibu’s land. Factors for halting Route 64 included the high cost

for property acquisition, on top of the high costs of constructing tunnels

and excavating in Malibu’s mountainous terrain, the position of the

Van Nuys Airport, which the freeway had to cross, and persistent

ecological concerns.

(Source: CSUN Special Collections: CA 64 - The Valley’s Right of Way to the Beach, 12/6/2022)

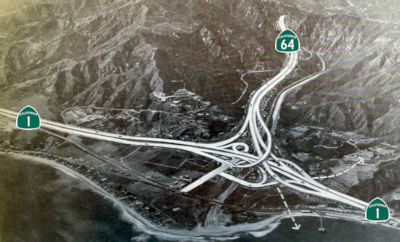

With respect to the Malibu portion of the route, Whitnall was also involved.

Whitnall recognized that Los Angeles was comprised of dozens of separate

but interconnected communities and proposed a network of four freeways

radiating from the center of Los Angeles to the satellite communities,

including the San Fernando Valley and Malibu. In 1958 plans for the

Whitnall Freeway were released with a route through Decker Canyon. By

1963, the route was moved to Malibu Canyon and was officially designated

Route 64. Plans emerged that included filling in the entire canyon and

building the freeway on the newly-created land. In February 1964, the

California Highway Committee held a public meeting to discuss the plan to

transform PCH into a freeway from Malibu Canyon Road to Point Mugu. A map

of the route shows the freeway running through the middle of Malibu Park.

The figure to the right, from 1963, shows the proposed interchange with

the Pacific Coast Freeway (Route 1) in Malibu. A 10-year battle ensued to

stop the freeway. It became a major issue in the fight for Malibu

cityhood. Campaign material from the unsuccessful 1964 Malibu

incorporation effort shows an artist’s rendering of the Malibu Civic

Center area entirely engulfed in a multilane freeway and multiple freeway

interchanges. In 1970 Malibu residents, citing ecological and economic

concerns, were able to have 7.5 miles of the proposed freeway deleted from

the master plan. Due to budget cuts and new environmental restrictions,

Whitnall Freeway fell years behind schedule.

With respect to the Malibu portion of the route, Whitnall was also involved.

Whitnall recognized that Los Angeles was comprised of dozens of separate

but interconnected communities and proposed a network of four freeways

radiating from the center of Los Angeles to the satellite communities,

including the San Fernando Valley and Malibu. In 1958 plans for the

Whitnall Freeway were released with a route through Decker Canyon. By

1963, the route was moved to Malibu Canyon and was officially designated

Route 64. Plans emerged that included filling in the entire canyon and

building the freeway on the newly-created land. In February 1964, the

California Highway Committee held a public meeting to discuss the plan to

transform PCH into a freeway from Malibu Canyon Road to Point Mugu. A map

of the route shows the freeway running through the middle of Malibu Park.

The figure to the right, from 1963, shows the proposed interchange with

the Pacific Coast Freeway (Route 1) in Malibu. A 10-year battle ensued to

stop the freeway. It became a major issue in the fight for Malibu

cityhood. Campaign material from the unsuccessful 1964 Malibu

incorporation effort shows an artist’s rendering of the Malibu Civic

Center area entirely engulfed in a multilane freeway and multiple freeway

interchanges. In 1970 Malibu residents, citing ecological and economic

concerns, were able to have 7.5 miles of the proposed freeway deleted from

the master plan. Due to budget cuts and new environmental restrictions,

Whitnall Freeway fell years behind schedule.

(Source: Malibu Surfside News, 4/22/2015, which also quotes this site; Facebook 11/25/2017; KCET Lost Landmarks, 6/28/2013)

Route 64 was not defined as part of the initial state signage of routes in 1934. It is unclear what (if any) route was signed as Route 64 between 1934 and 1964.

Status

Status

This route is unconstructed. The traversable local routing between Route 1 and US 101 is

Malibu Canyon Road; this portion was deleted from the Freeway and

Expressway system on 11/23/1970. There is no traversable local routing

between US 101 and Route 27. Between Route 27 and I-5, the traversable

local route is along Roscoe Blvd and Tuxford St. The portion between US 101 and I-5 was deleted from the Freeway and Expressway system on

1/1/1976. The route concept report recommends deletion of the route from

the highway system.

This route is unconstructed. The traversable local routing between Route 1 and US 101 is

Malibu Canyon Road; this portion was deleted from the Freeway and

Expressway system on 11/23/1970. There is no traversable local routing

between US 101 and Route 27. Between Route 27 and I-5, the traversable

local route is along Roscoe Blvd and Tuxford St. The portion between US 101 and I-5 was deleted from the Freeway and Expressway system on

1/1/1976. The route concept report recommends deletion of the route from

the highway system.

The 2013 Traversable Highway report notes:

This route isn't signed. It was assigned to what would have been the Malibu Canyon Freeway / Whitnall Freeway (on planning maps in 1965, shown on AAA maps as late as the mid 1980s), which left Route 5 near the Route 170/Route 5 junction, continued across the San Fernando Valley, crossing Van Nuys Blvd near Parthenia, Sepulveda near Chase, ending up about the level of Saticoy or Strathern. Just W of Bell Canyon, it turned to intersect the US 101 Freeway around Hidden Hills. It then crossed the Malibu hills approx. across Malibu Canyon (Las Virgenes) Road. The routing for this was never determined, and there is no assigned traversable route. The limits of the route inventory as of the 1970s was between US 101 and Route 5. The portion between US 101 and Route 1 had its adoption rescinded by the CHC on July 12, 1973. There is a nice discussion on the AARoads Forum that shows it on some maps of the era.

Naming

NamingThis would have been named the "Malibu Canyon Freeway" for the portion across Malibu Canyon, and the "Whitnall Freeway" for the portion across the San Fernando Valley. Maps based on the 1956 freeway plan show the route dividing at I-405. The Whitnall Freeway continued S (likely as Route 258) to go through Burbank, and then down along Western to Torrance. The remainder of Route 64 then continued to the Route 170/I-5 interchange. This was shown as the "Sunland Freeway".

The Whitnall Freeway was named for Gordon Whitnall, the former Los Angeles city director of planning. Part of

the reason for the naming could be that the route ran along Whitnall

Highway, an unusual divided street that was laid out in 1927 to be

part of a parkway network envisioned to dissect the Valley. In 1913,

Gordon Whitnall founded the Los Angeles City Planning Association, and in

1920, he established the Los Angeles City Planning Department. From

1920-1930, he was Director of Planning for Los Angeles, and from 1929-1930

was president of the League of California Cities. From 1932-1935 he was

the coordinator of the Committee on Government Simplification for Los

Angeles County. In 1941, Gordon and Brysis Whitnall established a planning

and government consulting firm in Los Angeles. Gordon Whitnall was an

instructor in Planning at the University of Southern California, and a

member of the American Society of Planning Officials, the American

Institute of Planners, the American Society of Consulting Planners, and

the International Fraternity of Lambda Alpha, Los Angeles Chapter.

The Whitnall Freeway was named for Gordon Whitnall, the former Los Angeles city director of planning. Part of

the reason for the naming could be that the route ran along Whitnall

Highway, an unusual divided street that was laid out in 1927 to be

part of a parkway network envisioned to dissect the Valley. In 1913,

Gordon Whitnall founded the Los Angeles City Planning Association, and in

1920, he established the Los Angeles City Planning Department. From

1920-1930, he was Director of Planning for Los Angeles, and from 1929-1930

was president of the League of California Cities. From 1932-1935 he was

the coordinator of the Committee on Government Simplification for Los

Angeles County. In 1941, Gordon and Brysis Whitnall established a planning

and government consulting firm in Los Angeles. Gordon Whitnall was an

instructor in Planning at the University of Southern California, and a

member of the American Society of Planning Officials, the American

Institute of Planners, the American Society of Consulting Planners, and

the International Fraternity of Lambda Alpha, Los Angeles Chapter.

(Source: Some information from Cornell University Library; Image source: Los Angeles Times, 11/5/1961 via Joel Windmiller, 1/18/2023, MyBurbank)

Other WWW Links

Other WWW Links Statistics

StatisticsOverall statistics for Route 64:

Pre-1964 Legislative Route

Pre-1964 Legislative RouteThe route that would become LRN 64 was first defined in the 1919 Third Bond Act as running from Mecca to Blythe. Mecca is S of Indio, near where present-day Route 86 (former US 99) and Route 111 diverge around the Salton Sea. The route ran across Box Canyon Road to join the current I-10 (former US 60/US 70) routing to Blythe. Note that this route had no connection to the remainder of the state highway system, nor to the state line, at the time (i.e., it didn't connect to LRN 26 in Indio/Mecca, nor did it extend to Arizona).

In 1931, Chapter 82 extended the route from Blythe to California-Arizona state line at the Colorado River and [LRN 64] to [LRN 26] near Indio. It was felt that, as a link in the transcontinental routing, the state route should extend from the state line to a conneciton with some other state route. It was noted in 1931 that approval of the requests of Arizona and California to place this route on the federal aid system had been granted by the Secretary of Agriculture. The bypass of Box Canyon opened in 1935.

In 1933, the route was extended further with two segments: (a) [LRN 2] near San Juan Capistrano to [LRN 77] near Lake Elsinore, and (b) [LRN 78] near Perris to [LRN 26] near Indio. Thus, in 1935, the route was codified as:

This definition was rapidly changed by Chapter 274 to make the last segment "A point near Shaver's Summit on that portion..."

In 1951, Chapter 1562 added the segment between LRN 77 near Lake Elsinore and LRN 78 near Perris to LRN 64, thus extending the first segment to terminate at LRN 78 near Perris.

This route was signed as follows:

This was Route 74, as was part of the 1934 signage number assignments. The portion between Lake Elsinore and Perris was also signed as US 395 until 1950.

This was originally signed as Route 740 (as of 1934), but was later resigned as Route 74.

Parts of this were signed as Route 195 sometime after 1934 between Mecca and Shaver's summit; that portion (likely Box Canyon Road) is not currently a state route.

From Shaver's Summit to Blythe: This was signed as US 60/US 70 from the summit to the Arizona state line, and is present-day I-10.

© 1996-2020 Daniel P. Faigin.

Maintained by: Daniel P. Faigin

<webmaster@cahighways.org>.