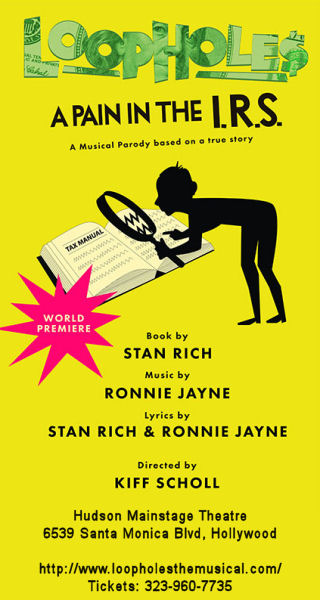

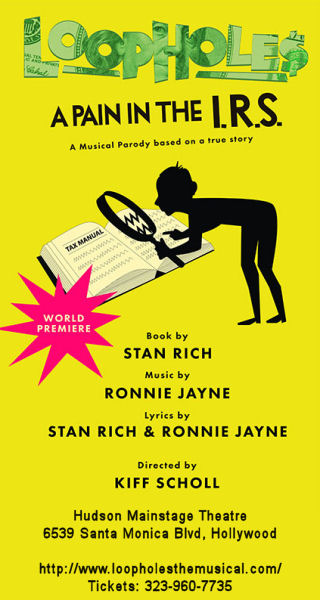

A few months ago, I heard about a new musical coming to Los Angeles (I don’t recall the source). The musical was called “Loopholes“, and it was a musical about taxes and the IRS. Now, I’m the son of two accountants (my dad was one of the last PAs in California; my mom one of the first woman CPAs), and I’m married to the daughter of a CPA. Naturally, I had to go see this show, and blocked off a date in my calendar. A month or so later ticketing for the show opens, and I quickly grab tickets for when we return from vacation. By now, you’ve probably figured out where I was last night 🙂 : I was at the Hudson Mainstage (FB) in Hollywood seeing “Loopholes“, a musical parody.

A few months ago, I heard about a new musical coming to Los Angeles (I don’t recall the source). The musical was called “Loopholes“, and it was a musical about taxes and the IRS. Now, I’m the son of two accountants (my dad was one of the last PAs in California; my mom one of the first woman CPAs), and I’m married to the daughter of a CPA. Naturally, I had to go see this show, and blocked off a date in my calendar. A month or so later ticketing for the show opens, and I quickly grab tickets for when we return from vacation. By now, you’ve probably figured out where I was last night 🙂 : I was at the Hudson Mainstage (FB) in Hollywood seeing “Loopholes“, a musical parody.

“Loopholes“, which features book and lyrics by Stan Rich (FB), and music and lyrics by Ronnie Jayne (FB), is ostensibly based on a true story of what happened to Rich in the 1980s and 1990s. The IRS had disallowed losses the author incurred from a tax shelter, but allowed only the gains. Despite numerous attempts to close the case, the IRS kept delaying and adding interest on the penalty. Eventually they IRS calculated a revised amount, which was 10% of the original demand. However, they still insisted on the full penalty. The battle went on for 15 years, until the IRS hit a block and could no longer go against the taxpayer. After resolving the situation, the taxpayer wanted to create a win-win situation… and so wrote a musical spoof of the situation. This was presented as “Taxpayer Taxpayer” until shortly after 9/11. It was then set aside for a decade, then reworked, updated, and adapted… resulting in this production.

The basic story above forms the plot of the musical, which was directed and dramaturged by Kiff Scholl (FB). Names, of course, were changed to protect… well, I’m guessing names were changed to avoid legal issues. The names chosen will give you quite an idea of the show. Our lead protagonist is Izzy Rich; his accountant is Harry Grim; the IRS agents are Eileen Holmes, Sheila Peel, and Howie Catchem; the therapist is Marsha Mellow. Yes, all of these names result in puns, which include the resultant beat for laughter (of which there was a lot in the audience).

These names reflect both the strength and the weakness of this show, which is hard to put into words. In many ways, the show reflects the author well. By this I mean that those who use (and sometimes abuse) tax shelters often try too hard; the attempt to get everything right and cross every “T” often raises flags that might not otherwise be raised. I’m guessing it is something like that which first caught the eyes of the IRS. Similarly, this show — which is funny and cute and entertaining — tries just a little bit too hard. There are points where it self-consciously pushes the humor, becomes self-referential, recognizes it is a show on a stage, highlights the fact that you just heard a joke, or goes for the obvious pun. These points become a little grating. Mind you, they aren’t enough to make this a bad show or destroy the entertainment value; rather, they just leave you with the “trying too hard” taste.

I don’t blame the author for this — this is his first show and his first musical, and it was written first as a musical comedy spoof for groups and to attempt to laugh and derive something positive from a bad experience. As a musical comedy spoof it does well. If it wants to transition into a musical with longer life — and perhaps a deeper message and commentary on the power of the IRS — it could likely do with a bit more reshaping. The director, Scholl, is also listed as the Dramaturge, and in this capacity I believe a little more could have been done to take off a bit of the earnestness edge. I think there is a great message and a great story here that could move this from a musical spoof to something much more, but that more work is required to turn this into something with greater gravitas and longevity.

But I’ll note that my opinion may be a little jaded due to my upbringing. You spend your life in a CPA office, surrounded with bad tax jokes, and they no longer become quite as funny. The audience sitting around me was truly enjoying this show (including the guy behind me who was singing along, even though he didn’t know the lyrics, sigh). There was lots of laughter, and even I found myself laughing out loud at a few of the jokes and scenes. I truly believe that I’m the oddity here — I think that this is a show that, despite its excessive earnestness, will make audiences laugh and will serve to entertain.

Another example of the “trying too hard” is found in the music: this is a 90 minute show, with no intermission. The program lists 35 songs — and this isn’t a sung-through opera. Many of these are only song snippets, and I’d estimate that perhaps 85-90% of them are parodies of other well-known songs. That doesn’t destroy the humor (after all, who can’t love “Sittin’ in the Schvitz” as a parody of “Putting On The Ritz”), but it’s odd for a musical that makes it appear as if it was a original musical. The few songs that I didn’t recognize as parodies were quite good (“Think Like a Winner”); again I found myself wishing the show had amped up the originality instead of going for the easy joke. Perhaps that’s part of the problem — scenes, characters, names were often there for the easy, funny joke, whereas I (trained after all these years for musicals with deeper meaning) was looking for something with a bit more depth. A uniform 5′ deep pool is still refreshing on a hot day, but it is safe; sometimes you want to jump off that diving board into the 10′ deep end.

If I was to summarize the book and music aspects of Loopholes, it would be that this show is funny and entertaining for what it is, but it left me wishing it was a bit more. I truly believe that there is a story here that can be musicalized, but to do so the author needs to decide what is the story he truly wants to tell — is the focus poking fun at the IRS, or is the story about “Izzy”‘s growth from a cold-business man to someone who finds a new attitude and a new relationship. The latter, if you look at this from high above, is the real story; the IRS is not the villain but the player who helps shape our leads journey. Telling that story — with truly new and original lyrics — could move this from the musical spoof/parody that it is into something much greater: a story of individual growth and attitude, with some humorous pointed commentary songs along the way. The verdict? Funny and entertaining and great, with some seeds that — if nurtured properly — can turn this into much more.

Part of what makes the presentation entertaining is the cast, who are fun and entertaining and a joy to watch — plus they all sing well. If the cast has a problem, overall, it is more in the direction — again, it tries a little too hard. The cast seems someone conscious that they are on a stage and are trying to make the audience laugh. Relax, and have fun kids. Luckily, the problem appears a bit less in the lead positions: Bruce Nozick (FB) as Izzy Rich and Caryn Richman (FB) as Dr. Marsha Mellow. Nozick brings a gentle humor to Izzy (as well as a lovely voice). He permits you to see both the businessman and the exasperation. As for Richman: She was wonderful to see on stage (full disclosure: I’ve enjoyed her acting since I first saw her on New Gidget; I’m amazed at how she has seemingly not aged since then (whereas I’ve … well, let’s say I was much younger then)). She sang well, emoted well, and related to the other characters well — and was just fun to watch.

In supporting roles (on the Izzy side) were Perry Lambert (FB) as Harry Grim and Julia Cardia (FB) as Brenda, Izzy’s secretary. Lambert was great as the accountant and quite funny in his role. His scenes as the Rabbi and in the steamroom were great. He also sang and moved well. I’m sure I’ve seen him in a past show, but I can’t put my finger on it. Cardia as Brenda was surprising. I think her best moments were when Harry brought in the backup singers, and she would watch them and slowing move in, joining in on the actions. Subtly funny, which is the humor I tend to like.

The primary IRS agents (although they played other roles as well) were Brad Griffith (FB) as Howie Catchem (also: the Wolf, Willie Nelson); Camille Licate (FB) as Eileen Holmes (also Nicole Kidme); and Taji Coleman (FB) as Sheila Peel (also Mrs. Lamaz). Griffith was fun to watch — he had a wonderful warmth with an undertone of evil — just what you need for an IRS agent 🙂 . Licate seemed to be enjoying herself as Eileen — the newbie IRS agent. She projected an aura of fun and naivete, singing strongly and clearly enjoying being on stage. Coleman performed well in her roles but there was a little something missing last night that I couldn’t pinpoint — she didn’t have the same energy and enthusiasm as the rest of the cast. My wife thought it was just her characters; my guess is that she was just having a slightly off night — and that happens sometimes. Irrespective of that, all three worked well together in their main IRS roles and were a fun team.

Rounding out the cast in multiple ensemble roles were Ryan Brady (FB) as Sam Flushing / IRS Supervisor / Pig #3 / Pete Rose / Bailiff and Nora King (FB) as Jude Gleo Grief / Pig #1 / Lois / IRS Receptionist. Brady had a nice warmth to him, and was hilarious as the plumber in “Flush It Down”. Please pass me the brain bleach for that rear dancing shot :-). King caught my eye the minute I saw her on stage — she just radiated enthusiasm and fun and happiness to be her characters — and that’s what I love to see. She was just wonderful in all her roles, and especially how she rocked the towel in the steambath scenes and rocked the gavel in her courtroom scenes.

Music was provided by the co-lyricist, Ronnie Jayne (FB), who served as musical director and on-stage accompanist. Lindsay Martin (FB)’s choreography worked reasonably well. There were a few points where it came off as a little forced, but I think that goes to the whole “trying too hard” vibe I picked up and discussed earlier. Overall, the movement worked well and fit the book and plotline. Rita Cofield (FB) was the stage manager, assisted by Ashley D. Clark/FB.

Turning to the technical: The set design was by Charles G. Sleichter and worked well in its simplicity. There was a backdrop that supported some projections, and two side panels that identified location or hid major props. Add a desk, and that was essentially it… but it worked. The lighting design by Donny Jackson (FB) worked well to establish the mood, and was otherwise non-obtrusive. The sound design by David B. Marling (FB) provided good sound effects. Murray Burn‘s costumes worked well and established the characters well; I particularly liked the little touches such as the green in all the IRS costumes. Casting was by Raul Clayton Staggs (FB). Publicity was by Kuker & Lee. Loopholes was produced by Theatre Planners (Racquel Lehrman and Victoria Watson); Bobbe Rothbart/FB was the co-executive producer.

Loopholes continues at the Hudson Theatre through Sunday, May 17. Even though it tries too hard, it is genuinely funny and entertaining and well worth seeing. Tickets are available through Plays411; discount tickets may be available through Goldstar and other sources.

[ETA: This show is a great example of the intimate theatre battle in Los Angeles. No, I don’t mean to paint AEA as the evil IRS, and the pro99-ers as trying to find loopholes. Rather, this is a production in an intimate theatre by a non-membership company, a theatre with more than 50 seats, by a non-profit. It features a mix of AEA and non-AEA actors (and AEA actors on both sides of the pro99 debate). It is precisely the type of production that would be hurt by the new rules, because they would have to pay minimum wage to the 7 AEA actors in the show. Given labor laws, the remaining 3 actors would also have to be paid minimum wage, because you cannot have “volunteers” doing the same job as employees (and from what I saw, they were certainly professional). Add in the creative designers, factor in theatre rental and the fact that many tickets are not full price but discounted via Goldstar, Plays411, LA Stage Tix, or other sources… and this would be a money loser. Yet it is shows like these that need to get off the ground; shows like these that need the dramaturgy and audience feedback to move forward. I Love 99 (FB) is a community of people that love LA’s intimate theatre and want to save it: AEA actors, non-AEA actors, creatives, technical people, stage managers, producers, critics, and audience members working together. LA has built a unique community thanks to the 99 seat plan: let’s figure out how to move the community forward in a plan that benefits all stakeholders. Follow us on Facebook, and learn about what you can do from our web page.]

[ETA: This show is a great example of the intimate theatre battle in Los Angeles. No, I don’t mean to paint AEA as the evil IRS, and the pro99-ers as trying to find loopholes. Rather, this is a production in an intimate theatre by a non-membership company, a theatre with more than 50 seats, by a non-profit. It features a mix of AEA and non-AEA actors (and AEA actors on both sides of the pro99 debate). It is precisely the type of production that would be hurt by the new rules, because they would have to pay minimum wage to the 7 AEA actors in the show. Given labor laws, the remaining 3 actors would also have to be paid minimum wage, because you cannot have “volunteers” doing the same job as employees (and from what I saw, they were certainly professional). Add in the creative designers, factor in theatre rental and the fact that many tickets are not full price but discounted via Goldstar, Plays411, LA Stage Tix, or other sources… and this would be a money loser. Yet it is shows like these that need to get off the ground; shows like these that need the dramaturgy and audience feedback to move forward. I Love 99 (FB) is a community of people that love LA’s intimate theatre and want to save it: AEA actors, non-AEA actors, creatives, technical people, stage managers, producers, critics, and audience members working together. LA has built a unique community thanks to the 99 seat plan: let’s figure out how to move the community forward in a plan that benefits all stakeholders. Follow us on Facebook, and learn about what you can do from our web page.]

Dining Notes: A wonderful find if you are seeing shows at the Hudson, the Blank, or the Complex (hint: remember this for Fringe Festival) is Eat This Cafe (FB), which is on the corner and is part of the Hudson complex of theatres. Although not on their online menu, gluten-free bread is available. They have wonderful salads and sandwiches. Note also that the Hudson’s cafe often has gluten-free muffins.

Ob. Disclaimer: I am not a trained theatre critic; I am, however, a regular theatre audience. I’ve been attending live theatre in Los Angeles since 1972; I’ve been writing up my thoughts on theatre (and the shows I see) since 2004. I do not have theatre training (I’m a computer security specialist), but have learned a lot about theatre over my many years of attending theatre and talking to talented professionals. I pay for all my tickets unless otherwise noted. I believe in telling you about the shows I see to help you form your opinion; it is up to you to determine the weight you give my writeups.

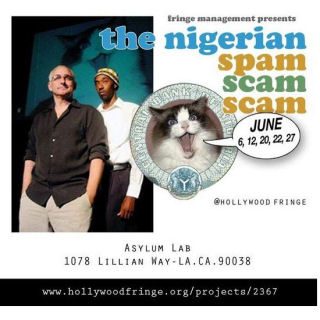

Upcoming Shows: Our next theatre is Tuesday night, when we’re going to the alumni performance of Alice – The Musical at Nobel Middle School. This is followed by “Words By Ira Gershwin – A Musical Play” at The Colony Theatre (FB) on May 9. The weekend of May 16 brings “Dinner with Friends” at REP East (FB), and may also bring “Violet: The Musical” at the Monroe Forum Theatre (FB) (I’m just waiting for them to show up on Goldstar). The weekend of May 23 brings Confirmation services at TAS, a visit to the Hollywood Bowl, and “Love Again“, a new musical by Doug Haverty and Adryan Russ, at the Lonny Chapman Group Rep (FB). The last weekend of May brings “Entropy” at Theatre of Note (FB) on Saturday, and “Waterfall“, the new Maltby/Shire musical at the Pasadena Playhouse (FB) on Sunday. June looks to be exhausting with the bounty that the Hollywood Fringe Festival (FB) brings (ticketing is now open). June starts with a matinee of the movie Grease at The Colony Theatre (FB), followed by Clybourne Park (HFF) at the Lounge Theatre (FB) on Saturday, and a trip out to see the Lancaster Jethawks on Sunday. The second weekend of June brings Max and Elsa. No Music. No Children. (HFF) at Theatre Asylum (FB) and Wombat Man (HFF) at Underground Theatre (FB) on Saturday, and Marry Me a Little (HFF) by Good People Theatre (FB) at the Lillian Theatre (FB) on Sunday. The craziness continues into the third weekend of June, with Nigerian Spam Scam Scam (HFF) at Theatre Asylum (FB) and Merely Players (HFF) at the Lounge Theatre (FB) on Saturday, and Uncle Impossible’s Funtime Variety & Ice Cream Social, (HFF) at the Complex Theatres (FB) on Sunday (and possibly “Matilda” at the Ahmanson Theatre (FB) in the afternoon, depending on Hottix availability, although July 4th weekend is more likely). The Fringe craziness ends with Medium Size Me, (HFF) at the Complex Theatres (FB) on Thursday 6/25 and Might As Well Live: Stories By Dorothy Parker (HFF) at the Complex Theatres (FB) on Saturday. June ends with our annual drum corps show in Riverside on Sunday. July begins with “Murder for Two” at the Geffen Playhouse (FB) on July 3rd, and possibly Matilda. July 11th brings “Jesus Christ Superstar” at REP East (FB). The following weekend is open, although it might bring “As You Like It” at Theatricum Botanicum (FB) (depending on their schedule and Goldstar). July 25th brings “Lombardi” at the Lonny Chapman Group Rep (FB), with the annual Operaworks show the next day. August may bring “Green Grow The Lilacs” at Theatricum Botanicum (FB), the summer Mus-ique show, and “The Fabulous Lipitones” at The Colony Theatre (FB). After that we’ll need a vacation! As always, I’m keeping my eyes open for interesting productions mentioned on sites such as Bitter-Lemons, and Musicals in LA, as well as productions I see on Goldstar, LA Stage Tix, Plays411.

As I wrote in the previous post, I just concluded a week as Local Arrangements Chair for the ACSAC conference. Part of my responsibility was to coordinate some form of dinner entertainment. Luckily, the Hollywood Fringe Festival made that easy, for it was there that I discovered The Nigerian Spam Scam Scam, the duologue based on a true incident.

As I wrote in the previous post, I just concluded a week as Local Arrangements Chair for the ACSAC conference. Part of my responsibility was to coordinate some form of dinner entertainment. Luckily, the Hollywood Fringe Festival made that easy, for it was there that I discovered The Nigerian Spam Scam Scam, the duologue based on a true incident.

This morning, as I was getting ready to write up last night’s show at the Colony, my mind was swirling about mathematics and theatre. I was thinking about tiers and when shows could go to contract; about discussions I had had with Barbera Beckley before the show about audiences and what they could and would pay. I was thinking about the whole AEA kerfuffle, and I’ve realized that we may have it wrong — and a lot of this is because we keep trying to build things on dependent factors without data. Before I could tackle my writeup, I had to get this out of my head.

This morning, as I was getting ready to write up last night’s show at the Colony, my mind was swirling about mathematics and theatre. I was thinking about tiers and when shows could go to contract; about discussions I had had with Barbera Beckley before the show about audiences and what they could and would pay. I was thinking about the whole AEA kerfuffle, and I’ve realized that we may have it wrong — and a lot of this is because we keep trying to build things on dependent factors without data. Before I could tackle my writeup, I had to get this out of my head.

A few months ago, I heard about a new musical coming to Los Angeles (I don’t recall the source). The musical was called “Loopholes“, and it was a musical about taxes and the IRS. Now, I’m the son of two accountants (my dad was one of the last PAs in California; my mom one of the first woman CPAs), and I’m married to the daughter of a CPA. Naturally, I had to go see this show, and blocked off a date in my calendar. A month or so later ticketing for the show opens, and I quickly grab tickets for when we return from vacation. By now, you’ve probably figured out where I was last night 🙂 : I was at the

A few months ago, I heard about a new musical coming to Los Angeles (I don’t recall the source). The musical was called “Loopholes“, and it was a musical about taxes and the IRS. Now, I’m the son of two accountants (my dad was one of the last PAs in California; my mom one of the first woman CPAs), and I’m married to the daughter of a CPA. Naturally, I had to go see this show, and blocked off a date in my calendar. A month or so later ticketing for the show opens, and I quickly grab tickets for when we return from vacation. By now, you’ve probably figured out where I was last night 🙂 : I was at the