“All children, except one, grow up. They soon know that they will grow up, and the way Wendy knew was this. One day when she was two years old she was playing in a garden, and she plucked another flower and ran with it to her mother. I suppose she must have looked rather delightful, for Mrs. Darling put her hand to her heart and cried, “Oh, why can’t you remain like this for ever!” This was all that passed between them on the subject, but henceforth Wendy knew that she must grow up. You always know after you are two. Two is the beginning of the end.” — The Adventures of Peter Pan, J. M Barrie.

“All children, except one, grow up. They soon know that they will grow up, and the way Wendy knew was this. One day when she was two years old she was playing in a garden, and she plucked another flower and ran with it to her mother. I suppose she must have looked rather delightful, for Mrs. Darling put her hand to her heart and cried, “Oh, why can’t you remain like this for ever!” This was all that passed between them on the subject, but henceforth Wendy knew that she must grow up. You always know after you are two. Two is the beginning of the end.” — The Adventures of Peter Pan, J. M Barrie.

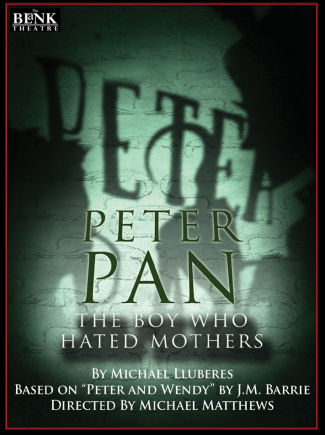

Growing up is on my mind in many ways. First, my daughter has just completed her first year at UC Berkeley, and is no longer the little girl. My wife is up in Berkeley picking her up and bringing her home. This led directly to the second thing that put growing up on my mind: while they were out I took the chance to go to Hollywood and see the Ovation-recommended play “Peter Pan: The Boy Who Hated Mothers” at the Blank Theatre in Hollywood.

Most people are familiar, yet not familiar, with J. M Barrie‘s Peter Pan. First and foremost, forget the Disney adaptation. I’ve actually never seen it, but I’m pretty sure it was Disney-fied and lost some elements of the story. My familiarity with Pan comes from the 1954 musical with book by J. M. Barrie, and music by Jule Styne, Moose Charlap and lyrics by Carolyn Leigh, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green. The story in Peter Pan: The Boy Who Hated Mothers hewed very close to the story in the 1954 musical (no surprise, as both used Barrie’s book as the basis) — in face, there were points where Michael Lluberes‘s script almost seemed word for word with the older musical (this was especially true in the opening nursery scenes). But there were also some significant differences — the major one being the catalyst in the story. In both the Disney version and the 1954 musical, there were three children who go off with Peter: Wendy, Michael, and John. In this version, there is only Wendy and John; Michael had died some unspecified time earlier at an ambigous age (the script makes you think 5-6, the props make you think it was while he was an infant). Michael’s death is the reason for discussing Peter Pan: Does Peter take the souls of children who die too early? Is he a real boy? Is he a boy lost in childhood? It is never made clear.

This Peter Pan, unlike many of the other versions (and I’m intentionally ignoring the prequel Peter and the Starcatchers and the sequel Hook), is a drama and is not played either for laughs or for the children. That’s not to say there isn’t humor in the piece; rather, it means level of the story is not simplified for children. Peter is petty and mean; he is an immature little boy thinking only of himself. Whereas the musical and the Disney version leave one with the message that one grows up only if one wants to, and that you need to embrace the child in you… this play leaves a very different message indeed. This is where the subtitle of the play comes in.

This play is titled Peter Pan: The Boy who Hated Mothers. The subtitle is important. One might ask: why, if Peter hated mothers, did he go to the effort to bring Wendy back as a mother for himself and the lost boys? Why does the period in Neverland revolve around the presence of Wendy as the mother… even to the point of where Capt. Hook (who is the reflection of the grown Peter) talks about the importance of the mother and as the mother as Peter’s weakness? The answer is that Peter’s relationship with mothers was that of wanting one, but of making choices that always seemed centered around himself and hurting mothers. This becomes especially poignant at the end of the play. We all remember how the musical ends: Peter comes back annually to Wendy to bring her back to Neverland for a week in the Spring; as Wendy grows up he does the same thing with Wendy’s daughter, Jane. In fact, the play ends exactly as the book ends:

“As you look at Wendy, you may see her hair becoming white, and her figure little again, for all this happened long ago. Jane is now a common grown-up, with a daughter called Margaret; and every spring cleaning time, except when he forgets, Peter comes for Margaret and takes her to the Neverland, where she tells him stories about himself, to which he listens eagerly. When Margaret grows up she will have a daughter, who is to be Peter’s mother in turn; and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless.”

The last line of the play mentions how this is heartless — and just think about this: Having someone come in and take your daughter away — every year, unthinkingly — is the act of someone who doesn’t feel the pain of a mother, and essentially hates them. Peter also takes away from Jane Darling and the children the last physical reminder of Michael — and I’m sure there are some aspects of hatred in that action as well.

The play also has a number of commentaries about growing up. Peter refuses to grow up, even though he is clearly a man in a physical sense (although with a baby’s skin and teeth). I saw this as saying that although Peter may grow up someone physically, he remained mentally and emotionally immature — and there are far too many men today who are the same. All the other “lost boys” eventually found their way to maturity (and Lluberes script actually describes how they matured)… but not Peter. Whereas other versions portray remaining a child as a good thing, this play gives the impression that it is somehow wrong — that remaining immature can hurt the others around you, and in your immaturity you won’t see the pain it causes (for when you are immature, you think only of yourself … in fact, a sign of maturity is starting to think and care about others around you). Wendy, although a little girl, is mature before her age. John is maturing with the help of Wendy. Peter never grows up. It’s not something to crow about.

The play does retain the one thing that always made me uncomfortable: the involvement of the audience in the saving of Tinkerbell after she drinks the poison. This time, it is having the audience shout out their belief in fairies with the lights out, but it is a hook that is also present in the musical version. Perhaps I don’t like it because I’ve never had the imagination to truly believe in fairies (which is why I’ve always been in the role of fan-at-a-distance, not the fanboy fanaticism many get. I’d love to be able to believe in fairies again; alas, I think I’m too grown up.

This version of Peter Pan works especially well because of the excellent direction of Michael Matthews and the excellent performance of the cast. Matthews kept the cast small, forcing most of the background players (the lost boys) to double as pirates and other characters. When combined with the limitations of the black box theatre, this plays up the emphasis of the Neverland side of the piece as being a large effort in Make Believe — pretending many things that are not real are fully real. One comes out asking the question: Was Peter real? A true question for the ages. LA Stage Week has a nice writeup on the genesis of this version.

The cast does an excellent job at making this all become real. In the lead positions are Daniel Shawn Miller as Peter Pan and Liza Burns as Wendy Darling. Miller’s Peter is childish and angry, strong and unthinking, and decidedly not mature. He doesn’t play Pan with the spritish-nature that most of the actresses has given (Peter is traditionally played by a woman); he is that mean little boy who only thought about himself. Still, Miller’s Peter does have his tender side, especially when playing father to the Lost Boys. Burns’ Wendy is much more mature. In fact, you can sense that she wants to do more with Peter and have a deeper (perhaps adult) relationship with him, but he never understands what she is hinting in. A typically clueless man-boy! Wendy’s pretend mother highlights the disciplinary aspects of being a mother, but you can see that underlying love and concern for the Lost Boys. Burns’ portray of Wendy does a great job of bringing out both the mature and the childish, often turning from one to the other on a time (as children growing up will do). At one moment she is playing; at the next, she’s remembering her mother and thinking about the pain she is causing. Contrast this with Peter: he never thinks about the pain he causes — he happily takes actions that hurt adults.

Miller and Burns are supported by an excellent ensemble. As John Darling, Benjamin Campbell mostly blends in with the Lost Boys,but especially in the closing scenes he shines as you can see his maturity beginning. Trisha LaFache doubles as both Mrs. Darling and Capt. Hook. This casting creates a different impression than the traditional approach (which has Wendy’s father doubling for Hook): the notion of a female captain lusting after little boys is very disturbing, especially with some of the implications the script creates. LaFache is versatile as both characters, bringing out both the mother and the devious Captain. The remaining ensemble members double as both Boys and Pirates, as well as other Neverland characters. Amy Lawhorn plays the lost boy Nibbs, the pirate Bill Jukes, as well as Tiger Lily and (essentially). Tinker Bell. Each comes off with a clearly different persona, and you get the sense that Amy is having fun with all the different characters. You see the same thing with Jackson Evans (Tootles/Smee) and David Hemphill (Slightly/Starkey). Evans’ Smee is particularly fun — you can see that he has a very different attitude towards Hook than does any of the crew. All of the actors were just remarkable, and appeared to truly be having fun with their roles. They are also very creative and versatile, switching from character to character with ease.

Technically the production is a very clever hoot. The set design by Mary Hamrick was remarkably clever, making great use of the Blanks’ black box space. She created a raised floor with compartments underneath, simple bedroom furniture that with imagination easily became places on the island or the ship, and wonderful use of flowing silk for water or blood. Her creative approaches to the crocodile were also fun. She was aided in this with the property design of Michael O’Hara. Kellsy Mackilligan‘s costume design was equally clever, creating the run-down clothing of children lost on an island, yet still retaining the echo of Victorian bedclothes. Rebecca Kessin‘s sound design was particularly noteworthy — usually sound design focuses on amplification, but I really noticed Kessin’s design in the sound effects and ambient noise. This was particularly emphasized during the ship scenes where the stereophonic effects and the creaking made my mind think we were actually on a ship. The lighting design by Tim Swiss and Zack Lapinski was also strong — both in the use of overhead lights to create the mood and establish scenes, but even more in the use of floor and prop lighting to create the magic, and the use of lighting to create Tinkerbell in a way I haven’t seen before. Dialect coaching was by Coco Kleppinger and was mostly good, creating the British flavor of the story. However, at one of two points the heavy accent combined with fast narration made it hard to follow the words. Sondra Mayer provided the fight choreography, and it is always fun to see swordplay on stage. The production was stage managed by Rebecca Eisenberg (who also served as assistant director), assisted by Jillian Mayo. It was produced by Noah Wyle, Sarah A. Bauer, Stephen Moffatt, and Matthew Graber; Dawn Davis, Emily Mae Heller (who we know from Temple Beth Torah); Even Martin, and Noelle Toland were associate producers. Daniel Henning is the founding Artistic Director of the blank; Ed Murphy is the Managing Director, and Noah Wyle is the Artistic Producer.

Peter Pan: The Boy Who Hated Mothers runs through June 2 at The Blank Theatre and is well worth seeing. Tickets are available through the Blank Box office, and may be available through Goldstar.

Seeing this production reminded me of how impressed I am with the productions at the Blank. If the Colony subscription dies (we still don’t know), the Blank is on my short list of places that might replace that subscription (other places include the Falcon Theatre in Burbank or the Odyssey in West LA). However, none of these has the mid-size feel we got with the Colony or its predecessor, the Pasadena Playhouse. I’ve considered the Playhouse if Colony dies, but their season just doesn’t excite me. I am open to suggestions.

Dining Notes: Dining out before the show was at Eat This Cafe, which is across the street from The Blank and part of the building that houses the Hudson Theatre. It is a simple place, but very good and very nice. If I’m attending theatre at the Hudson (they are soon doing Rent, which is a possibility), the Blank, or any of the theatres nearby on Santa Monica, I will be back to Eat This.

Upcoming Theatre and Concerts: Sunday brings “Falling for Make Believe” at The Colony Theatre. The last weekend of May brings “To Kill a Mockingbird” at REP East and The Scottsboro Boys” at the Ahmanson Theatre. June brings “Priscilla – Queen of the Desert” at the Pantages, and (tentative) Sweet Charity“ at DOMA (although DOMA may be replacing it with “Nine“). June will also bring a Maria Muldaur concert at McCabes. I’m also considering Rent at the Hudson Theatres or A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum at the Hillcrest Center for the Arts in Thousand Oaks. July is currently more open, with “9 to 5 – The Musical” at REP East in the middle of the month, and “Legally Blonde – The Musical” at Cabrillo at the end of the month. August is currently completely open due to vacation planning. I’m also keeping my eyes open as the various theatres start making their 2013 season announcements. Lastly, what few dates we do have open may be filled by productions I see on Goldstar, LA Stage Tix, Plays411, or discussed in the various LA Stage Blogs I read (I particularly recommend Musicals in LA and LA Stage Times).