I’ve been trying to avoid political posts since the post-mortem post, but something in today’s paper just got to me. In an article about the Speaker of the House, John Boehner, and his desire to stand firm on taxes there is the line:

I’ve been trying to avoid political posts since the post-mortem post, but something in today’s paper just got to me. In an article about the Speaker of the House, John Boehner, and his desire to stand firm on taxes there is the line:

Even though election-day exit polls showed most Americans have said they prefer the president’s approach — asking upper-income households to pay higher taxes — Boehner believes his party similarly won a mandate against tax hikes as the majority party in the House.

Boehner’s belief that he has a mandate based on the house majority is wrong. House seats are essentially winner take all: If a Republican is elected to represent a district, that does not mean that the district all agrees with that candidate. Further, the “winner take all” effect for congressional districts is amplified by the effect of Gerrymandering. In most states, districts have gone to particular parties because they were specifically drawn to permit that party to win. In some districts, there was no opposition to vote for. That, my friends, is not representational government. The article on Gerrymandering pointed out that overall, more Democratic votes for congress were received than Republican votes, and that wouldn’t surprise me either.

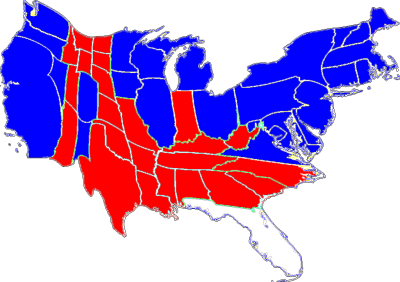

By the way, this goes both ways. Looking at the electoral map and numbers (332 to 206), you might think there was a strong Democratic mandate. You would be wrong. Here’s a map (h/t David Bell) that shows the states deformed to reflect population:

I have finally caught up with a map showing Florida blue.

I agree with you on the point that people tend to misinterpret mandates and misinterpret things in general — particularly in politics.

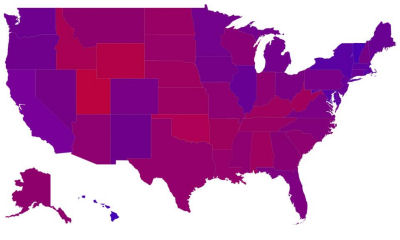

But your other point seems to be that it is easy to misinterpret things by looking at colorful maps. That is true also. But it applies to Mr. Bell’s purple map as much as it does to the red/blue maps. None of these maps tell the whole story.

Polls have shown a trend for quite some time that when asked about opinions on specific issues without regard to ideological or party labels, people respond with answers that are overwhelmingly progressive and that correspond far better with Democratic positions than Republican ones.

There are numerous distortions that keep this from being reflected in election results. Factors related to psychology, marketing, political maneuvers (such as the gerrymandering you mentioned), and any number of other things all come into play and one of these factors are reflected on maps.

Another big distortion is our rather antiquated way of running elections in the first place. We allow people to make one choice over several others but we don’t set it up to measure the weight that someone gives to the particular choice they make. Or for that matter, whether they would make the same choice or apply the same weight to their choice when other contributing factors are considered.

Humans are pretty bad at dealing with complex systems in general, particularly with our political processes. One reason is that much of our political infrastructure is set up as though an 18th century agrarian society was still a reality. There’s countless cases of issues being framed and treated as completely separate and having nothing to do with each other when that’s not the reality at all. There’s also a lot of false dichotomies and other logical fallacies built into the system itself as well as in how people vote.

You also assume that people know what they really want and make rational choices based on what they really want. A wide body of research in psychology shows pretty overwhelmingly that that assumption isn’t true.